| Philip Glass and librettist Christopher Hampton have revised their “Appomattox” — first seen in 2007 in San Francisco — to reflect contemporary political concerns. Originally, the piece’s first half dealt with the end of the Civil War in 1865. The second part showed episodically how the hopes for national reconciliation and — particularly — equality of opportunity for African Americans fell tragically short.

Ironically, “the Party of Lincoln” has in recent decades led the legal charge against fully enfranchising minority voters — a battle that should have been won with President Lyndon Johnson’s Voting Rights Act of 1965. The steep challenges to voting that Republican state legislatures have recently enacted prompted Glass and Hampton to make the second act more current for the opera’s première in the nation’s capital.

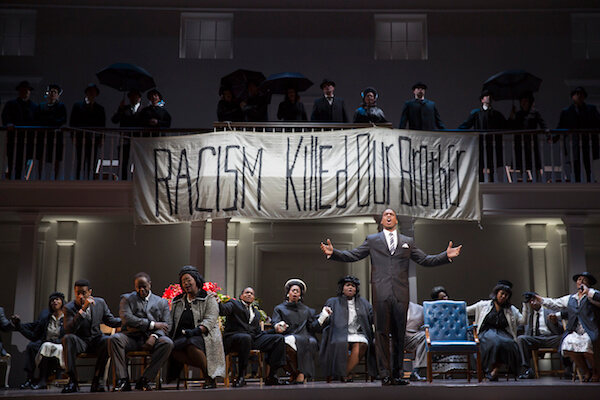

It tells a compelling story, admirably timely in political significance. Tazewell Thompson’s Washington National Opera production, a large, able cast, and incisive musical leadership from Dante Santiago Anzolini (replacing Dennis Russell Davies at late notice) made for a strong evening of theater, clearly attended closely by a more than usually racially diverse audience. It was exciting November 21 to see performers (WNO’s splendid young Sarastro, Soloman Howard, and veteran heroic baritone Tom Fox, droll and powerful) embodying Martin Luther King and President Johnson take the final curtain calls together and embrace. So, as an event and statement, “Appomattox” proved worthwhile and stirring.

Glass and Rossini operas in Washington

The score, however, proved musically rather banal and Glass-generic, save for a few choice, effective scenes — usually those employing the fine WNO chorus and/ or an embedded text, like the opening “Tenting on the Old Campground,” King’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic” speech, and Johnson’s televised endorsement of voting rights. Too often, Glass employs the same “driving rhythm of history” devices that Poulenc’s “Dialogues” borrowed from “Boris Godunov” to start a scene illustrating an historical point but then gives its participants no vocal or thematic idiolect. Largely, we see exhibits in a pageant.

Besides the two leads, a few singers made strong impacts in their paired roles: young dramatic soprano Melody Moore, who led the piece’s women in a stirring, hymn-like finale; the characterful, incisive Richard Paul Fink; fiery lyric mezzo Chrystal E. Williams, with superb diction; and the resonant, experienced David Pittsinger, playing the ‘noble’ Lee and white supremacist Edgar Ray Killen. Perhaps Act Two should have concentrated more on African Americans; the libretto carries more than a hint of Hollywood-style centralizing lionization of sympathetic whites.

Coincidentally, Boston Lyric Opera was concurrently performing — in a strong production by R. B. Schlather — his 2000 chamber opera “In the Penal Colony,” a Kafka-based work that prophetically reflects on issues of capital punishment and the legitimacy of sites like Guantanamo Bay. It redounds to Glass’ credit that he has sought subjects speaking to such fundamental socio-political issues.

Washington Concert Opera has been doing fine work of late. Its “Semiramide” on November 22 proved a nice chance to hear Rossini’s fine score — or at least much of it, since Antony Walker made some whacking cuts — but the performance didn’t quite live up to its demands or WCO’s highest standards. Both orchestra and chorus sounded slightly under-rehearsed; Walker at times uncharacteristically drove his forces for volume and speed that sometimes covered the solo singing.

Australian soprano Jessica Pratt, first heard stateside in 2012 at Caramoor, made a creditable stab at the title role, despite it being written low for her natural comfort zone. A clean-voiced singer with a well-honed technique, Pratt reminded me in good and bad ways of Ruth Ann Swenson. Pleasing to hear save for a pallid lower register, she ventured some exciting high interpolations but didn’t invest much in the proud Babylonian’s words. The audience seemed thrilled; I wanted more fire and verbal point.

Vivica Genaux, as ever a dashing, committed artist alert to keen verbal and musical phrasing, sang Arsace. Anyone expecting a Marilyn Horne or Ewa Podles sound went wanting, but on her own more lyrical terms Genaux offered a complete portrait, with astonishing agility and imaginative — usually downward — decoration.

As the Indian prince Idreno, occasional Met tenor Taylor Stayton sang with style and ease at the extreme top. His tone isn’t exactly dulcet but he’s a capable artist worth hearing; he deserved his deleted first aria. Wayne Tigges, a sturdy bass-baritone with Handel in his past, still has much to offer, but no longer in this particular repertory: his Assur too often sounded constrained and approximate. Walker would have done better to deploy the elegant bass Evan Hughes (here Oroe, the High Priest) as Assur and used stentorian, impactful Wei Wu (here Nino’s ghost) as Oroe. Hughes’ voice has grown slightly in volume and he attacked his music with style and nuanced dynamics. He and Genaux would serve this opera best in slightly smaller venues.

Upcoming productions of note in Washington include WNO’s “Lost in the Stars” with Eric Owens — a superb staging and fantastic leading performance carried over from Glimmerglass 2012 — and general director Francesca Zambello’s intriguing “Ring” cycle. Catch the third cycle, starring Nina Stemme and cast with other strong singers including Christopher Ventris, William Burden, Jamie Barton, Elizabeth Bishop, Alan Held, and Melissa Citro. The finely tailored Vocal Arts series hosts recitals by David Daniels, Javier Camarena, and Julia Bullock.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.