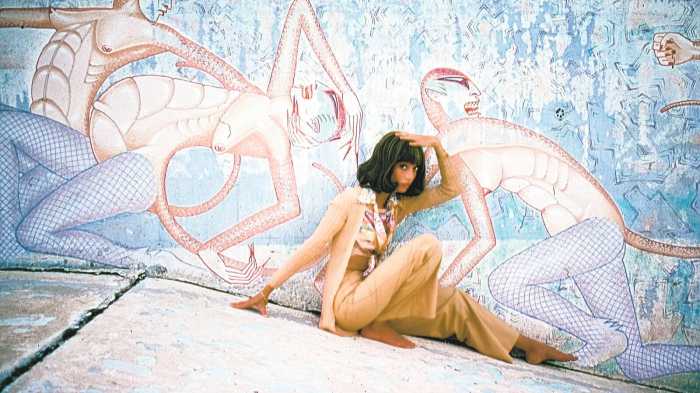

Adam Tendler’s January 19 program at (Le) Poisson Rouge showcased the range of his touch and the inventiveness of his phrasing. | GREG PARKINSON

At a recent concert featuring the serial music of Aaron Copland (1900-1990), Adam Tendler played “Piano Fantasy” — a piece I first heard 60 years ago. William Masselos was the pianist on that occasion, and he hammered home the stiff angularity of the music as if force-feeding the audience something they hated.

So I was surprised and delighted when Tendler made the same notes sound familiar and likable, even delicate. His phrasing turned even the most complex and discontinuous passages into satisfying music. It sounded like a wild, beautiful bird trying to escape from its cage to fly home, deep in the forest. Those thorny textures and complex rhythms I remembered from 1957 became poetic in Tendler’s hands.

The “Serial Copland” program, performed January 19 at Bleecker Street multimedia art cabaret venue (Le) Poisson Rouge, began with a gentle piece: 1921’s “Petit Portrait (ABE).” It created a calm atmosphere that contrasted sharply with the blunt assertiveness of the “Piano Variations” that followed. Third on the program, “Quartet for Piano and Strings,” was a kind of sorbet between “Piano Variations” and “Piano Fantasy.”

Thorny textures rendered poetic by stunning virtuosity in performance by Adam Tendler

Three members of JACK Quartet — Austin Wulliman (violin), John Pickford Richards (viola), and Jay Campbell (cello) — joined Tendler for a precisely intoned, lyrical, and tender reading. Then came the main course, “Piano Fantasy,” Copland’s intense journey into atonality. It wasn’t a strict 12-tone composition (and neither were any of the others), but the effects of atonality were all there. Tendler – who will perform at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music on February 10 – gave this formidable work a shape and momentum that held the audience’s unwavering attention for the duration of the 30-minute piece. There wasn’t a single extraneous sound to be heard in the large room, filled to capacity with people eating and drinking — and not a cough or a whisper from the crowd standing at the bar.

Tendler, a scholar as well as a virtuoso, wrote comprehensive program notes that can be accessed online (bit.ly/serialcoplandprogramnotes). They give a clear and entertaining narrative of Copland’s sporadic affair with serialism.

In 1930, when Copland wrote “Piano Variations,” the influence of Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) was keenly felt in Western classical music. He declared the demise of tonal function and reorganized the way notes could be sequenced in a musical phrase.

No composer could ignore this new concept. Tonal classical music, principally in the German tradition — from the early 18th through early 20th centuries — was the template against which Schoenberg rebelled. Some critics think it was World War II and the Holocaust that provoked this revolution. I give credit for Schoenberg’s becoming a pioneer of music composition to the philosophy of history put forth by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831). Hegel propounded a dialectical scheme in which an idea, a thesis, competes with another idea, its antithesis, until the two merge as a synthesis. That synthesis becomes a new thesis. Schoenberg’s rules for tone rows and the unfamiliar sounds they created, the antithesis of tonal music, resolved in a new synthesis: serialism.

Between pieces on the program at (Le) Poisson Rouge, Tendler played recordings of Aaron Copland’s genteel voice, which described, with quiet earnestness, how Schoenberg’s aesthetics influenced his own method of composition. I think Copland’s voice also communicated the ordeal he experienced in being accepted by the academic establishment, who were the guardians and promulgators of Schoenberg’s ideas.

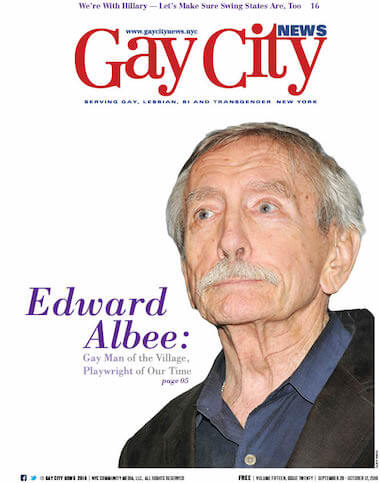

Being gay and closeted played a role in Copland’s desire to be approved by the music establishment at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. It was his way of finding a place in academic high society that disapproved of homosexual behavior.

Neither Copland nor Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) ever said publicly that they were gay, even though it was obvious. “You don’t rub their noses in it,” Thomson told me when I asked why he wouldn’t support efforts to stop the spread of AIDS.

In the early ’70s, I had dinner with Copland in his home upstate, with Michael Tilson Thomas, David Del Tredici, and Robert Helps. Copland couldn’t have been nicer. A short time later I attended a concert of his music and afterwards approached him. “Aaron, I loved your music.” He looked at me without smiling and replied, “Call me Mr. Copland.”

Robert Helps, a brilliant pianist who played complex modern music with uncanny ease, had a deep fear of being “discovered” as gay. He studied music composition with Roger Sessions and was famous for his performances with Bethany Beardslee of Schoenberg’s “Pierrot Lunaire” and Milton Babbitt’s “Partitions.” Whenever Babbitt came to hear him play at Yale, Helps warned me not to say anything remotely gay in Babbitt’s presence. Denial was a major part of our lives back then, and it was a source of excitement as well, to see what we could get away with in such austere company. Our conversations were loaded with gay allusions and innuendos. One might say that Copland alluded to serialism in his music more than he employed it methodically — Schoenberg’s sounds seeped into Copland’s music.

Ivy League composers, theorists, and teachers back in the ’50s were the bastion of propriety with regard to Schoenberg’s theory. Copland, despite his failure to fully embrace the technique, was nevertheless accepted as a practitioner of it in the elite coterie of academic serialists. I think it was because of his enormous popular success with pieces like “Appalachian Spring” and “Fanfare for the Common Man.” Maybe a musicologist will someday write about how some gay composers absorbed the aesthetics of 12-tone music without really committing to its formal demands.

Every time I’ve heard Adam Tendler play modern American piano music, he has surprised me with the range of his touch and the inventiveness of his phrasing. His performance at (Le) Poisson Rouge was no exception. A few months ago, in a recital of John Cage’s piano (and toy piano) music at Lincoln Center, Tendler talked about Cage’s indications in the score to play as soft as possible. It reminded me of sitting in the top balcony at Carnegie Hall, hearing Vladimir Horowitz play pianissimo; every note had a “ping” that carried to the back of the house.

The strings in the first and third movements of Copland’s “Quartet for Piano and Strings” also had gossamer moments. Most impressive was their perfect intonation of delicate phrases. Tendler, Austin Wulliman, John Pickford Richards, and Jay Campbell seemed to breathe together. Aaron Copland was a gentle genius, and his atonal music, meticulously performed by this ensemble, demonstrated that humanity.

Visit adamtendler.com and jackquartet.com for upcoming performance dates, music, and other information.