Lyra McKee’s first love was journalism. The youngest of six, she was born in 1990, in Northern Ireland, to a Catholic family headed by a single mother. She grew up just off Murder Mile, the area in Belfast where nearly a quarter of the 3,700 killings took place during “the Troubles.”

To know McKee, you must first know something about the Troubles. They began in 1968 when Northern Ireland’s government — pro-British, mostly Protestant — started crushing the civil rights protests of the minority Catholic population, which had been shut out of jobs and political power. The resulting partisan fury between Catholic “Republicans” who wanted a free Ireland, and Protestant “Unionists,” proud to remain in the UK, metastasized into paramilitary groups led at one extremity by the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and the other by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). Their bombings and killings lasted 30 years until 1998, when the Good Friday Agreement was signed.

McKee was a “Ceasefire Baby,” one of thousands of children meant to thrive, free from violence and factional terror. But with “peace,” and the assurance that Northern Ireland remained in the United Kingdom, the UK Government settled into a policy of imperial neglect, further impoverishing the six northern Irish counties still under its control.

So McKee, like most of the Belfast she knew, Catholic or Protestant, grew up poor. She was born premature; as a child she had to wear a corrective eye patch and take remedial reading classes. A shy, nerdly creature — and budding queer — she spent her early school years in quiet misery.

But at 14, McKee began to take an interest in her school newspaper. She joined Headliners, a charity supporting young journalists, and at 16, won Sky News’ Young Journalist Award for a story on suicide rates in North Belfast. She began, as she would continue, sifting hard truths from the cold cases of Northern Ireland’s past — and from the despair and dearth of jobs of its present. If 3,700 people died during the Troubles, McKee wrote, by 2014, 3,709 had died by suicide — the majority, Ceasefire Babies.

Although quick to see social inequities, McKee valued people over causes and harbored little fondness for groups like the New IRA. Speaking for much of her generation, she wrote, “I don’t want a United Ireland or a stronger Union. I just want a better life.”

Even after discovering journalism, McKee spent her teens in secret agony, fearing God’s wrath for her attraction to women. When she was 20, she tried to tell her mother, but, “sobbing and shaking,” couldn’t get the words out. Finally, her mother asked, “Are you gay?”

“Yes, mummy, I’m so sorry.”

To which her mother replied, “Thank God you’re not pregnant.”

McKee later described this incident in an essay, “Letter to My 14-Year-Old Self,” which became a small international sensation and was made into a short film. “It won’t always be like this,” she tells her audience, “It’s going to get better.”

It did. Her writings on queerness and Northern Ireland were published in an array of outlets such as Buzzfeed News, The Private Eye, Mosaic, and The Belfast Telegraph. Her article, “Suicide Among the Ceasefire Babies,” appeared in The Atlantic. The news aggregator Mediagazer hired her to edit; she started The Muckraker, a news blog; she gave a TEDx talk on the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting; she signed a two-book contract; in 2016, she was named one of the “30 Under 30 in Media” by Forbes.

McKee also fell in love with Sara Canning, a nurse at a Derry hospital, and moved to Derry to live with Sara. They were soon embraced by an ad hoc assortment of women in Derry’s LGBTQ community, a “girls’ club” who laughed, talked, hung out. McKee bought a ring and told a friend she was planning to pop the question. Then, on the night of April 18, 2019, while covering a protest, she was shot in the head by a bullet fired by someone in the New IRA. She died on her way to the hospital.

LOST, FOUND, REMEMBERED

McKee wrote hard and long, but she only made it to age 29. So far, two books have been culled from her legacy. “Angels with Blue Faces,” only about 16,000 words, investigates the 1981 IRA murder of Unionist MP Robert Bradford. Sales from the book will go, as she intended, to Paper Trail, a Belfast non-profit that helps people find information about their loved ones lost to the Troubles. “Angels with Blue Faces” is a valuable book if you want a sense of the toxic collusion that complicates Northern Ireland’s history. But the book was released before its time and badly needs an editor. If you want to hear McKee’s real voice, read “Lost, Found, Remembered: Lyra McKee in Her Own Words.”

This collection of McKee’s essays and articles offers published writings on Belfast, gayness, and journalism, as well as work not before published. Excerpts from “The Lost Boys,” McKee’s unfinished book about eight Belfast boys who went missing during the Troubles, reveal how game-changing her political journalism was becoming:

She wrote, “I know very well how the Troubles masked other crimes; how women, children, and vulnerable people were harmed because child abusers and killers and men who beat their wives don’t stop doing what they do because there’s a war on… [S]ometimes, they carry on because the war has turned them into a ‘protected species’ — like an IRA or UVF member who raped women but were too valuable to the organization to be punished…”

She wrote of her friends in the Ceasefire generation, both Protestant and Catholic: “Peace was an acquaintance rather than a friend. But we were alive and more likely to die by our own hands than somebody else’s.” She wrote about her grandparents’ generation, people who had been in the IRA, or in the Royal Ulster Constabulary. She interviewed ex-prisoners from either side, people who had spent “20 years in a 4 x 4-foot cell” for their part in killings. She worked to comprehend all of that now:

“I couldn’t stand in front of a woman who’d watched her husband be gunned down, in front of their own children, perhaps in their own living room, and tell her that the men who’d done it were more complex than evil and more human than her grief would allow…”

WRITING BEYOND WORDS

It’s now time to declare my own politics. I’m a leftist, a queer, an anti-racist. My own writing includes articles on US political prisoners, some white anti-imperialists; others members of the Black Panther Party — people who, like the IRA, engaged in armed struggle. I would, in theory, agree with Irish Republicans that Britain should get the hell out of Ireland. But I have also been struck to the heart, humbled, and fired up by the beauty in just about every piece McKee has written on this subject.

McKee, in fact, has helped me to become a prison abolitionist. She wanted things to get better; prison abolition holds that caging people for decades only deepens divisions — of race or religion or class or politics — and can’t help but make things worse.

Abolition offers the prospect that people who have caused and incurred great harm can meet, talk; can see each other, in the hope of working out new definitions of justice. This close attention to the truth of individual lives is the essence of McKee’s journalism. That’s why the worth of McKee’s writing is beyond — even her own — words. She didn’t have time to explore and write about things like prison abolition or restorative justice. But she chose journalism because she had to discover, not which side was “right,” but the truth that breathes beyond borders.

On April 22, 2019, the Monday after McKee’s death, the Derry girls’ club — who came to be known, via a BBC documentary, as “The Real Derry Girls” — marched to the building that housed Saoradh, a militant Republican organization linked to the New IRA. All Catholic but one, the women soaked their hands in bright red paint and pressed “bloody” handprints over the political murals on the building’s walls. Reporters caught some of their statements:

“People have been afraid to stand up to people like this, we are not afraid“; “They are not a representation of republican people in this town”; “They need a life, not a gun put in their hands…”

A day later, in a statement given to The Irish News, the New IRA offered “our full and sincere apologies to the partner, family and friends of Lyra McKee.”

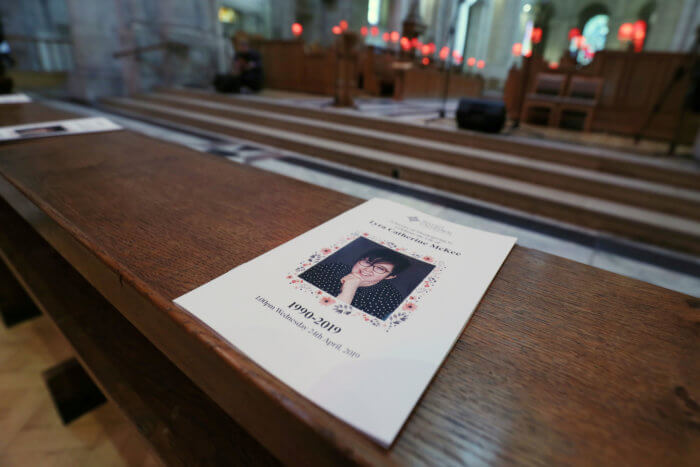

With McKee’s death, UK politicians paid more notice to Northern Ireland. Then-Prime Minster Theresa May, along with MPs from Westminster, Dublin, and Belfast, attended her funeral. Addressing the crowd, Father Martin Magill acknowledged the UK’s presence, asking: “Why in God’s name does it take the death of a 29-year-old woman with her whole life in front of her to get to this point?” He received a standing ovation lasting several minutes.

So far, three men have been charged with McKee’s murder; a fourth with rioting and possession of gasoline bombs. The public, McKee’s family, her friends — certainly Sara Canning, who spoke of McKee as “the love of my life, the woman I was planning to grow old with” — are demanding justice.

The “justice” they receive will depend on the way Northern Ireland chooses to create it. Justice will be either a step toward a small but profound healing, or one more angry division inside a country beleaguered by its brutal past, as well as the impending realities of Brexit. Do things really get better? One way or another, McKee’s theory will be tested.

McKee’s books:

“LOST, FOUND, REMEMBERED: LYRA MCKEE IN HER OWN WORDS” | London, UK: Faber & Faber, 2021 | 186 pp, 978-0571351459 | paperback

“ANGELS WITH BLUE FACES” | Belfast, UK: Excalibur Press, 2019 | Approx. 1600 words; 9781910728529 | Ebook only; pbk not available in US