For the past 27 years, close to 70 million Iranians have been living under an oppressive theocracy which, among other things, limits the access of its citizens to the international community, subjects them to harsh punishments for the most venial offenses, and deprives them of their basic social and political rights. Gay men and lesbians are particularly vulnerable, since the regime considers homosexuality among the most serious crimes, on a par with murder, armed robbery, and rape.

However, the Iranian sexual minorities are not the only group at the receiving end of such systematic oppression. The Iranian regime has shown the same zero-tolerance for various religious, ethnic, and political minorities in Iran. For the ruling mullahs in Tehran, the name of the game is conformity.

Fortunately, the Iranian civil society is not sitting silent. Over the past decade, numerous grassroots movements have risen in Iran. Most of these groups are independent, small, and loosely organized associations of concerned citizens trying to make piece-meal improvements in their lives, away from any political controversy. These activists present the biggest challenge to the ruling establishment. By demanding a more just environment, these everyday heroes are the main force behind the possibility of social change in this fortress of tyranny.

Most Iranian activists have one thing in common—little interest in being pushed by outsiders (unlike their LGBT Russian and Polish counterparts who encourage involvement from Western activists in their quest for freedom). Perhaps the examples of neighboring Iraq and Afghanistan have taught them that only a social consensus, and not an outside intervention, can bring about a better future for their country.

For many Western activists, outraged by the situation of their brothers and sisters in Iran, it is only natural to want to do anything within our power to condemn the Iranian regime and its homophobic policies, and insist that our own governments call for change in Iran. Yet, it is imperative that we seek routes for change that will not endanger our colleagues in Iran, will have an impact, and will support their work in the way they wish to do it.

In a country under constant military threat from the West and a long history of Western colonization, our well-intended public calls for change are often perceived in a very different light. Many Iranians fear that outrage from the West over persecution of LGBT people carries with it yet another verbal attack against their national and religious identity, which could soon be followed by a military action. In the words of Mitra R., an Iranian-American activist who participated in our July 19 panel on Iran, “the actions of Western activists have had a missionary tone, seeking to act as saviors and to convert Iranian sexual minorities to a Western cultural worldview and way of being ‘gay’ that is based on identity, visibility, and outness.”

The International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission is fully committed to assisting our Iranian colleagues. We believe that inaction and silence in the face of such horrendous and consistent persecution in Iran is not an option for human rights activists. Yet, it is also not an option to respond without working very closely with the Iranian community, both in the country and around the world for the simple reason that it is their lives at stake, not our own.

So what does this mean in terms of action? First, we believe that public discussions that involve Iranian activists at the center of the discussion is a critical first step—like the “teach-ins” of the 1960s that helped spawn the anti-war movement. Learning about society in Iran, the sentiments of activists working within the country, as well as those outside, and how to work with them rather than parallel to them is essential. Second, we are committed to supporting the strength and capacity of Iranian human rights groups in whatever way we can, as we are well aware that it is their voices, not ours, that must prevail. Exile groups like the Persian Gay and Lesbian Association are important to maintaining connections with individuals and civil society groups in the country. Third, we will continue to document the abuses faced by Iranian LGBT people to ensure that their stories and conditions are visible to other civil society groups in and outside of Iran.

Working in this way may not provide the immediate gratification of a demonstration at the Iranian Embassy or insistent letters to George Bush to take action. In fact, the process of working with Iranian LGBT activists and responding to their specific needs and requests may prove to be long and painstakingly slow to activists in democratic societies where our public voice is a given and our visibility so much less likely to provoke arrest and punishment—even death. But for those of us eager to find a quick fix to this problem, the ongoing civil war and chaos in Iraq serve as a sobering reminder that culturally insensitive solutions can only inflict more suffering on the very people we intend to assist.

LGBT Iranians, and their fellow citizens, are entitled to humane treatment by their government. Iranian society has the potential to move in that direction, and we are here to work closely with our Iranian colleagues and their allies to ensure that their voices are being heard across the globe.

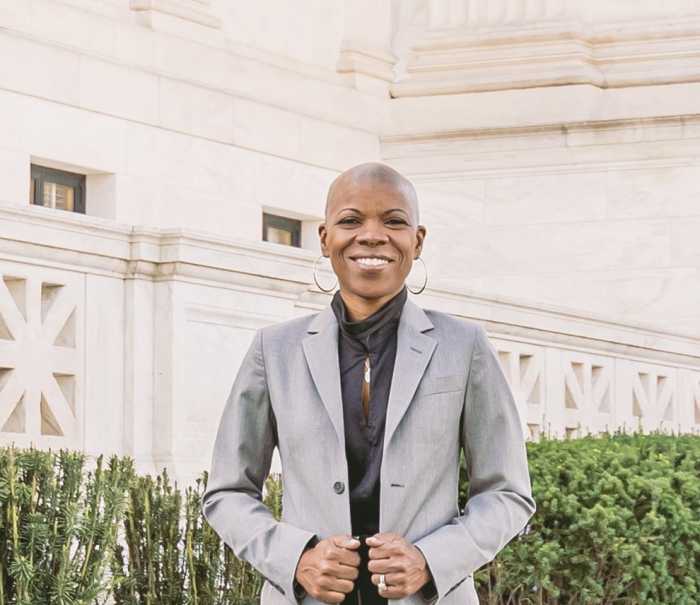

Paula Ettelbrick is the executive director of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission, a U.S.-based global organization that engages in and supports global sexual and gender rights advocacy.

gaycitynews.com