HOP’s march director Julian Sanjivan, Detective Carl Locke, the NYPD’s LGBTQ liaison, Patrol Borough Manhattan South Executive Officer James Kehoe, Patrol Services Bureau Executive Officer Fausto Pichardo, and Joseph Gallucci, the commanding officer of the NYPD’s citywide counterterrorism unit, at the June 5 town hall. | DONNA ACETO

The organization that produces New York City’s annual Pride Parade and related events first considered a controversial new route for this year’s parade in December 2016, but throughout the first six months of 2017, as it was negotiating a resistance contingent in last year’s parade, it never told activists in that contingent or the broader community that it was contemplating a change going forward.

“My concern is that [Heritage of Pride] has not consulted with the rest of the community,” said Sheri Clemons, who is a stalwart member of the LGBTQ community who regularly turns out for protests and meetings, during a heated June 5 town hall that was organized by Heritage of Pride (HOP), which produces the parade, the mayor’s office, and senior members of the NYPD. “You have to listen to the community and that also means reaching out and engaging… Everybody should have known that these changes would be disturbing.”

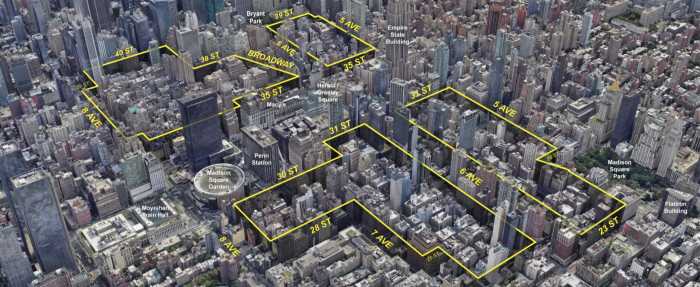

HOP shortened and reversed the 2018 parade route so it runs south on Seventh Avenue from Chelsea then east on Christopher and Eighth Streets before heading north again on Fifth Avenue to end at 29th Street. Contingents are limited to 200 people and the number of floats and vehicles has been reduced. HOP is expecting 43,000 marchers this year as opposed to 55,000 last year. HOP is making all marchers wear wristbands, a requirement that led to “No wristbands” chants during the town hall.

At town hall, angry response over lack of community input, long-undisclosed planning

In meetings held last month, HOP said that discussions with the NYPD and other city agencies about the new parade route began in August 2017. HOP ultimately presented the NYPD with six choices and the agency selected the route. While HOP meetings are public, it never announced the new route until after the final decision was made in January 2018. The December 2016 date was first acknowledged publicly in a PowerPoint presentation made at the June 5 town hall, which was held to explain the new march route.

Sheri Clemons holds up a sign expressing her displeasure with Heritage of Pride’s community engagement. | DONNA ACETO

The fact that discussions, even if they were only internal HOP deliberations, had begun months earlier and that the group had multiple opportunities to inform the community and activists as they negotiated the 2017 resistance contingent inflamed feelings at the town hall, which was already going to be contentious.

Ken Kidd, a longtime LGBTQ activist, was the lead negotiator for last year’s resistance contingent, organized to respond to the election of Donald Trump. He described the new route as a “stupid, small, rinky-dink route” and a “march to nowhere.” After the meeting, Kidd told Gay City News that “I was on the phone with them four times a week” and there were other chances for HOP to disclose the plan.

“That does not speak well to transparency,” Kidd said during the town hall.

Out gay City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, whose district includes major portions of the parade route, including the West Village and Chelsea, told Gay City News he was not brought into any discussions of the changes.

As Gay City News was going to press, the newspaper learned that Erik Bottcher, Johnson’s chief of staff, met with the mayor’s office and four HOP officers on May 31. They agreed to a community planning process for the march route for 2019 that could result in the route changing again. HOP and a representative of Johnson’s office who spoke at the meeting did not disclose this at the town hall.

Julian Sanjivan, HOP’s march director, conceded Tuesday evening that the group had missed the mark.

“Could we have done a better job at it?” he said during the two-hour town hall. “Clearly, yes, we could have done a better job at it.”

Last year, the sole demand was for a resistance contingent at the front of the march. This year, a group of activists with deep roots in the LGBTQ and other movements organized as the Reclaim Pride Coalition (RPC) asked for a resistance contingent, a reduced corporate and police presence at the march, including two police-free zones in the West Village, an explanation for the new route, and that members of the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL) march without uniforms or weapons.

The Coalition members, who range in age from their early 20s to much older than that, were clearly not inclined to be generous, feeling that HOP has not been accessible. The longstanding complaint that large corporations dominate the parade is a central issue. Activists believe that HOP has torn the march from its roots in an anti-police riot and turned it into a commercial and a celebration.

“You think that making something public is the same thing as community engagement and it’s not,” said Jeremiah Johnson, a member of the Coalition. “You have to intentionally do that… My concern right now is that you guys are party planners with no sense of rebellion.”

For its part, HOP has responded that community groups and non-profits continue to make up 65 to 70 percent of the contingents in the parade and even the corporate contingents are made up of LGBTQ employees. Shortening the parade is not only an accommodation to the city, which must police and clean up after the parade, it is an accommodation to marchers who do not want to wait for hours to step off.

The new route is a test in anticipation of the far larger crowd expected next year for the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, which mark the start of the modern LGBTQ rights movement. The reasoning is that dispersing the crowd in Midtown, as opposed to the West Village, gives more public transportation options.

A panel comprised of HOP co-chair Maryanne Roberto Fine, Sanjivan, three senior NYPD officials, Matthew McMorrow from the mayor’s office, Detective Carl Locke, the NYPD’s LGBTQ liaison, Detective Brian Downey, GOAL’s president, and Lydia Figueroa, GOAL’s recording secretary, spent about 30 minutes presenting to the crowd of roughly 100.

When Sanjivan first mentioned the new route, it was greeted with hissing. Police officials and GOAL made presentations that were received politely. Audience questions and comments lasted about an hour and most of the heat was directed at HOP, though police and GOAL caught some flack. When panelists began to respond to the questions during the final 30 minutes of the town hall, there were repeated interruptions.

There were two sympathetic moments during the meeting. One came when Hannah Simpson, a transgender woman, praised the police.

Hannah Simpson, a transgender woman who expressed gratitude for the NYPD’s work. | DONNA ACETO

“What I can say is I’ve interacted with the NYPD on many levels, including sitting in on a hate crime investigation supporting a trans woman of color friend of mine,” Simpson said. “What you don’t hear about on the news are the thousands of officers who are saving lives and respecting us.”

The second came when Downey said, as he has before and as HOP has supported, that GOAL members would be marching in uniform.

“I will not dishonor Charlie Cochrane and Sam Ciccone by taking off those uniforms,” he said referring to two of the founders of the 36-year-old organization. That comment drew applause.