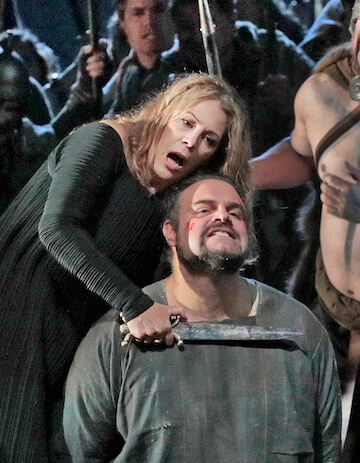

Dolora Zajick and Sondra Radvanovsky as Amelia in Verdi's “Un Ballo in Maschera.” | KEN HOWARD/ METROPOLITAN OPERA

Former bad-boy director turned respected grand seigneur David Alden made his Metropolitan Opera debut with a new production of Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera.” Alden overlaid his production with three parallel dramatic concepts, but they failed to coalesce into a compelling unified whole, instead adding layers of distracting artifice undercutting Verdi’s solid dramatic values.

Concept 1: “Mythical Metaphor.” A large painting representing the Fall of Icarus, the Greek youth who attempted to fly to heaven on waxen wings and fell to earth when they melted in the heat of the sun, served as the show curtain. It also hung over the action in an omnipresent ceiling fresco. Evidently it symbolizes Gustavo’s reckless, overreaching abuse of his power. The pageboy Oscar danced around during the prelude costumed in a pair of white wings as an Icarus/ Gustavo surrogate — even miming his fall to death.

This heavy-handed metaphor was compounded by one of the oldest and most tired tricks in the regie playbook, which was Concept 2: “It Was All a Dream.” This trope dates back at least to the Steerman’s dream in Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s mid-1970s “Flying Dutchman.” Before that there was Dorothy’s odyssey in “The Wizard of Oz” — some of you homosexuals may be familiar with that movie and its star, Judy Garland. The conceit reached its nadir in 1986 when Bobby Ewing stepped out of the shower on a season finale episode of “Dallas.”

After watching Oscar’s fallen angel dance, Gustavo falls asleep in an armchair during the prelude and dreams the whole thing. We do not see him wake up in the chair or step out of the shower at the end of the opera having gained greater self-knowledge of his fatal Greek hero hubris. So where all this was intended to go is beyond me.

Concept 3: “Hello Dalí!” The metaphorical and dreamlike elements are carried over into the surrealist landscape that Alden imposes on Verdi’s 18th century Sweden. “Ballo,” unlike Verdi’s other middle period opera, does not have one overriding dramatic mood or tinta but instead blends opera buffa elegance and gaiety with dark powerful drama. Alden apparently concluded that this shifting tone and underlying unease lent themselves to surrealism.

Paul Steinberg’s sets, with their skewed angles and mirrored surfaces, borrow from de Chirico and Dalí. Renato’s house resembled a nightmarish black and white box from “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” The bowler-hatted zombie chorus is costumed by Brigitte Reiffenstuel à la Magritte.

The action seems to be updated to the 1930s with the men in three-piece suits and Amelia wearing Adrian or Orry-Kelly evening gowns. However, Verdi’s action, based on an historical regicide, is very realistic and needs to be presented to the audience without artsy conceptual filters.

Alden was booed lustily at the opening night curtain calls. Unlike Piero Faggioni, the director of the previous overstuffed pageant of a Met production, Alden actually did have ideas about the opera. The problem is that there were too many and most were misguided.

He did, however, provide the singers with enlivening personal direction. I have never seen Marcelo Álvarez, the Gustavo, project more personality or move better on stage. Similarly, Sondra Radvanovsky can seem dramatically awkward and clueless when left to her own devices. Here, she riveted the audience’s attention from her first entrance to her anguished reaction to her lover’s murder at the final curtain.

But the production seemed to undercut dramatic credibility at crucial emotional moments. The gallows-heath set for Act II had the Falling Icarus canvas hanging over the action center stage. In the passionate climax of the great Act II love duet, the Icarus painting was raised and the back of the stage opened to show a desolate landscape with barren trees and telephone poles. Amelia and Riccardo sang their passionate avowals of love far apart on opposite sides of the stage. Wouldn’t it have made sense to start the scene with the desolate landscape and bring in the Icarus painting when the King loses himself in his self-destructive passion for Amelia, with the adulterous lovers coming physically closer together? It was as if Alden had a constant need to intervene between the audience and the work itself. The resulting effect of alienation drove the dramatic temperature below freezing.

Álvarez is yet another Latin lyric tenor pushing a sweet lyric voice to emulate the spinto power he was not endowed with by nature. He punches out the tone, breaking up the vocal line with bumpy phrasing. In Gustavo’s Act III romanza “Ma se m’è forza perderti,” Álvarez poured out the honeyed tone that established him as a leading lyric tenor more than 15 years ago.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky began rather stiffly as Renato/ Anckarström but rose to passionate heights in a nobly sung “Eri tu.”

Radvanovsky’s taut, dark soprano with its tense vibrato embodies the secret guilty passion that tears Amelia apart. She effectively used chest voice on the low notes, and an occasional metallic quality did not diminish the excitement and accuracy of her high notes.

Kathleen Kim has a buttery warmth in her tone that kept Oscar from turning into a squeaky soubrette automaton. Dolora Zajick, despite some loss of vocal power and thrust, still commands the brilliant high notes and deep contralto low notes with which Ulrica’s part abounds.

A fine group of singers and a spirited, precise conductor leading a world-class orchestra provided some heat and light. Fabio Luisi conducted with clarity and animation but during several ensembles the soloists and orchestra failed to come together for the tutti climax.

But these musical coordination problems were momentary. Dramatically, “Ballo” was all over the place and failed to come together throughout.