Dick Leitsch in the 2017 LGBTQ Pride Parade in Manhattan. | ANDY HUMM

Dick Leitsch, who as president of the Mattachine Society, a pre-Stonewall gay group, participated in the first act of gay civil disobedience in 1966, worked to end entrapment of gay men by the police, and wrote the first eyewitness report on the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, died June 22 in Manhattan after a year-long battle with cancer. He was 83.

On April 22, 1966, Leitsch, Randy Wicker, Craig Rodwell, and John Timmons set out to challenge the ban on serving alcohol to gay people in bars in New York by staging “Sip-Ins” at several watering holes — identifying themselves as homosexual and asking to be served. The Ukrainian-American restaurant in the East Village, notorious for not serving gay people, closed after getting wind that they were on their way. The bartenders at Howard Johnson’s and another joint named Waikiki frustrated their effort, serving them despite their declaration.

It was at the West Village’s Julius’ — at the time a “raided premises” (due to the recent arrest of a gay man there) and fearful of losing its liquor license — that the men were denied service in view of the media, despite the establishment’s history of being a quasi-gay bar since the 1950s. While LGBTQ people had demonstrated and even rioted before this, the Sip-In was the first act of targeted gay civil disobedience and it was successful. The State Liquor Authority dropped its holding that serving gay people made an establishment a “disorderly premises” — and, in fact, denied such a regulation ever existed.

The New York Times report on this historic action was headlined “3 DEVIATES INVITE EXCLUSION BY BARS.”

Pre-Stonewall pioneering activist, correspondent from the front was 83

That same year, Mattachine, led by Leitsch, worked with the new administration of Mayor John Lindsay, a Republican-Liberal who had been backed by progressives, to end police entrapment of gay men and stop police harassment of and raids on gay bars.

Mattachine made progress on these issues, but obviously didn’t prevent the mother of all gay bar raids at the Stonewall in the wee hours of June 28, 1969. Leitsch heard about it on the radio and hopped in a cab to get down there from his Upper West Side apartment, writing that night the first report on the Rebellion for the NY Mattachine Newsletter, later reprinted in the Advocate.

He wrote, “The police behaved, as is usually the case when they deal with homosexuals, with bad grace, and were reproached by ‘straight’ onlookers. Pennies were thrown at the cops by the crowd, then beer cans, rocks, and even parking meters. The cops retreated inside the bar, which was set afire by the crowd. A hose from the bar was employed by the trapped cops to douse the flames, and reinforcements were summoned. A melee ensued, with nearly a thousand persons participating, as well as several hundred cops. Nearly two hours later the cops had ‘secured’ the area,” though the Rebellion was to go on for five more nights.

“One middle-aged lady with her husband told a cop that he should be ashamed of himself. ‘Don’t you know that these people have no place to go and need a place like that bar?’ she shouted.”

Leitsch wrote that at first, “The crowds were orderly, and limited themselves to singing and shouting slogans such as ‘Gay Power,’ ‘We Want Freedom Now,’ and ‘Equality for Homosexuals.’”

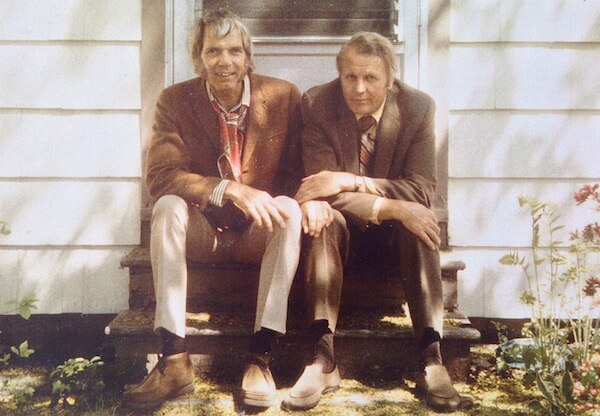

Dick Leitsch as a young man. | COURTESY OF MATT ALLISON

His account got more vivid, writing that a police car “bearing a fat, gouty-looking cop with many pounds of gilt braid chauffeured by a cute young cop, came through. The fat cop looked for all the world like a slave-owner surveying the plantation, and someone tossed a sack of wet garbage through the car window and right on his face. The bag broke and soggy coffee grounds dripped down the lined face, which never lost its ‘screw you’ look.” A “concrete block” landed on another police car.

After the cops seized and beat “a boy who had been doing nothing,” Leitsch wrote, “50 or more homosexuals who would have been described as ‘nelly’ rushed the cops and took the boy back into the crowd. They then formed a solid front and refused to let the cops into the crowd to regain their prisoner, letting the cops hit them with their sticks, rather than let them through.”

Leitsch’s final paragraph captured the confusion of police at the rebellion of a community they looked on with pity and contempt: “One of the most frightening comments was made by one cop to another, and overheard by a [Mattachine] member being held in detention. One said he’d enjoyed the fracas. ‘Them queers have a good sense of humor, and really had a good time,’ he said. His ‘buddy’ protested, ‘Aw, they’re sick. I like nigger riots better because there’s more action, but you can’t beat up a fairy. They ain’t mean like blacks; they’re sick. But you can’t hit a sick man.’”

When Lindsay called Leitsch to stop the Stonewall Rebellion, Leitsch told him, “Even if I could, I wouldn’t. I’ve been trying for years to get something like this to happen.”

Historian and activist David Carter — whose 2004 book “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution” is the definitive account of the ‘69 Rebellion — said that Leitsch’s activism effectively legalized gay bars and created the expectation on the part of LGBTQ people that they would be legally served.

“Without Dick Leitsch, there would have been no Stonewall,” he told Gay City News.

The Stonewall Rebellion accelerated the movement exponentially. Its historic significance is not just the fight back — which had happened before — but the way in which it led to immediate and ongoing activism. Leitsch told me — with only slight irony — “Before Stonewall I was the only gay person who was a leader. After Stonewall everyone was a gay leader.”

Richard Valentine Leitsch was born May 11, 1935 in Louisville, Kentucky.

“I always knew I was gay,” he said in an interview with Gay City News months before he died. He went to his first gay bar at age 18 — in 1953 — and “got picked up by this awful, awful queen” who had sex with him and then sent him a box of roses with a note declaring his love, he told the magazine Sexual Behavior in 1971. His mother “intercepted” the flowers, asked him if he was homosexual, and he said, “Yes” — very rare for those times. He had a priest cousin who had earlier told Leitsch’s parents that he thought their boy was gay, so they had read up on it. “They were very attuned and never made me feel guilty about it,” he recalled, though he did go to a doctor because he had heard “homosexuals were sick.”

“I kept looking in the mirror to see if my face was breaking out,” he said.

The psychiatrist, in the then-benighted profession when it came to gay people, attacked Leitsch’s parents and told him he could be “cured” but that it would take many years. Leitsch said his mother started screaming at the doctor, “How dare you try to make me feel guilty, make him feel guilty! How dare you try to ruin this boy’s life by giving him all this crap!”

A letter that former President Barack Obama sent to Dick Leitsch in March. | COURTESY OF MATT ALLISON

Leitsch left Louisville for Cincinnati and made it to New York in 1959. He told author Eric Marcus, “I wanted to get the hell out of Louisville and go someplace civilized. Because on Saturday mornings everybody would go to the movies and all the other kids wanted to be cowboys and firemen and whatever, space people. And I wanted to go to New York and smoke cigarettes and drink cocktails like Bette Davis. And goddamn it, I did it and they’re still not cowboys.”

You could say Leitsch was drawn into activism at Mattachine by love — by a desire to spend more time with his then-boyfriend Craig Rodwell, later the founder of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in the Village and the lead instigator of the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March in 1970 to commemorate Stonewall. Leitsch was at first reluctant to go to Mattachine because he had attended a meeting in 1962 only to be subjected to a lecture by psychotherapist Albert Ellis on how sick gay people were — a presentation that earned Ellis a standing ovation from the then mostly self-hating group.

In his ‘71 interview, Leitsch said that in the 1950s, “When you joined [Mattachine], you had to sign a pledge saying you wouldn’t swish, act sissy or ‘camp’ in public, and you wouldn’t have sex in public places. You had to promise to dress nicely and respect all racial and religious minorities. I think they were trying to make homosexuals super-good so we could be acceptable… It didn’t work too well.”

Mattachine was founded by the legendary Harry Hay in Los Angeles in 1950 and in Washington was headed by Frank Kameny, who had been engaging in unapologetic gay activism since the late 1950s. A militant Kameny speech in New York — urging gay people to fight for our rights the way African Americans were waging the Civil Rights Movement — inspired Leitsch to run for vice president of Mattachine/NY with Julian Hodges as president in 1965. Hodges, however, resigned within the year and Leitsch became the reluctant president — but he threw himself into the work.

“We thought we had to be more aggressive,” he told Sexual Behavior. “First of all, we had to admit we were homosexuals. Previously, everyone used a pseudonym — and they were all Greek… That just irked the hell out of me. If you’re a queer, say it.”

Leitsch said in ‘71, “I think the main goal of the movement is to help people get over the guilt inflicted on homosexuals… We do need sophisticated organizations to deal with job discrimination, tax inequities, sodomy law reform, etc.”

Leitsch was pre-deceased by Timothy Scoffield, his partner of 17 years, who died of AIDS in 1989. He is survived by his brother, Jack, and sister Joanne Williams, both of Louisville, numerous nieces and nephews, a host of friends and comrades, and admirers who include former President Barack Obama, who recently wrote him, “Our journey as a nation depends, as it always has, on the collective and persistent efforts of people like you.”

Leitsch’s funeral at St. Mary the Virgin on June 28, the 49th anniversary of Stonewall, was presided over by the church’s rector, Reverend Stephen Gerth, who said that Leitsch, an active member of the parish, embodied the dictum “If people don’t like you for who you are, they won’t like you for pretending to be what you’re not.”

Denny Meyer, a gay veteran activist, was at Leitsch’s funeral. He wrote on his blog that he worked up the courage to call Mattachine when he was 15 in 1964 and Leitsch, “who was used to calls from confused teenagers,” answered. Meyer went from Long Island to their offices “five floors above Herald Square in a dowdy old office building.” Leitsch, Meyer wrote, “greeted me in a kindly voice, knowing exactly why I was there without my having said a word. He turned me over to their ‘youth counselor’ Craig Rodwell who at age 26 was expert at calming young gay teens frightened of who they were. At the time, Rodwell had an older lover, in his 30s, named Harvey Milk, a downtown stockbroker whom no one had ever heard of at the time.”

Also mourning Leitsch last week was Steve Helfer, 71, who said, “He was the first gay man that I ever saw that was masculine. He was on a TV show that I saw when I was 14 or 15. I lived on Queens Boulevard and I was scared to death. I saw someone I wanted to model myself after.”

Matt Bomer (with glasses on), currently appearing in “The Boys in the Band” on Broadway, at the reception at Julius’ after Dick Leitsch’s funeral and interment. | ANDY HUMM

After his funeral and interment at St. Luke in the Fields where he will rest next to Christopher Street, a reception was held at Julius’, the site of the historic Sip-In and a 50th anniversary observance in 2016 that Leitsch and Wicker attended. Cheryl Williams, Leitsch’s niece, said that on a trip home to Louisville, she accompanied her uncle to the LGBT Center at the University of Louisville where Katy Garrison, the program coordinator, was introduced to him and, when told about his accomplishments, said, “‘We always knew we were standing on the shoulders of greatness.” That day, Leitsch spent a half hour talking to an entering gay freshman who has gone on to become a gay activist himself, Williams said, inspired by Leitsch’s example.

Randy Wicker, 80, the longest surviving veteran of the Mattachine, said, “Dick kept Mattachine alive. I left around ‘64, ‘65 after having gotten involved in ‘58.” He said he put Leitsch on a $100 retainer to supplement his meager income “because I felt guilty leaving him alone.” Leitsch had told me, “I had shitty jobs, but I mostly had a good time.”

Leitsch was asked in his 1971 interview what he felt about the line in “The Boys in the Band,” “You show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse.” “That’s the old 1930s guilt,” he said. “Gay life is like any other life — it’s what you make of it.”

In May of this year, Leitsch saw the current Broadway production of “The Boys in the Band” with its all-star out gay cast and was invited backstage to meet with them. Matt Bomer, who plays Donald, came to the reception at Julius’.

“On behalf of our show,” Bomer told Gay City News, “it was an honor to spend some time with him and that he was able to attend. We’re all eternally grateful for what he did.”