An abstract expressionist with a powerful vision explored light and found insight

In 1926, William De Kooning arrived as a young man in New York from Holland, got a job as a housepainter, and became friends with art scene luminaries like Gorky, Rosenburg, Hess, and Motherwell. In the years that followed, De Kooning became one of the most important painters of the Abstract Expressionist movement, along with Rothko, Newman, Pollock, and Kline.

In 1963, already an established figure in the art world for several decades, he moved full-time to the Hamptons, then still a rural enclave, where his work continued to expand as he absorbed the light and landscape of eastern Long Island. For the next four decades, he availed himself of the region’s special “double light” to follow his own vision of color.

A new show of De Kooning’s work at the Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea, curated by David Whitney, consists of 39 paintings documenting his stylistic transition from 1946 through 1988. The earliest works in the show are surrealist-influenced black and white paintings that hold an important key to the rest of his life’s work. These paintings made use of enamel house paint on board, a radical technique for the time, and wrestled with formal issues of modernism and biomorphic interior space. By stripping away color and imagery, they introduced his signature struggle with transforming line into form and form into line, and the spatial concerns that he pursued with compression, abstraction, and subversion within painting’s hierarchies.

A second gallery of works date from the early 60s through the mid-70s. These paintings demonstrate his gracious embrace of the influences of light and landscape in the years after he first began spending time on Long Island. The 1961 “Suburb in Havana,” with bold strokes of pinks, yellows, and blues evoking Latin-influenced stucco homes, is one of many examples of his obsession with spatial and surface tension. In contrast, “Screams of Children Come From Seagulls,” a 1975 oil on canvas, seduces with a weaving of line, color, and form in the ever-changing water and sky.

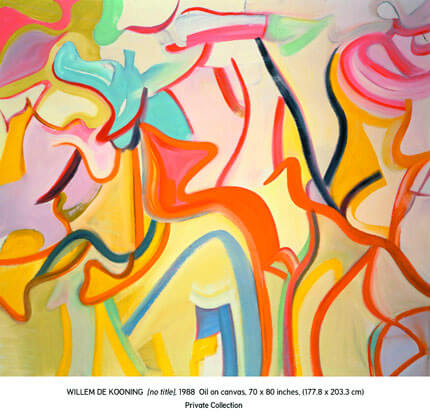

The main gallery contains De Kooning’s most startling paintings, from the end of his career, which have been surrounded with controversy ever since they came on the market in the 1980s. Detractors have argued that his assistant painted them or that they are evidence of the slow onset of Alzheimer’s already forcing him into artistic decline. The Gagosian exhibit, in contrast, places them in their appropriate context; set against an installation that highlights De Kooning’s genius, they emerge as the artistic pinnacle that they truly are.

On first glance, De Kooning, in these works, seems to have sacrificed juicy surfaces for flatter, subtler transitions, but I would argue that he had to do this so that color and line could be distilled and function as one pure and powerful gesture, forcing the physicality to collapse into unified nuisances of light and form. All his other works were leading to these shorthanded, labanotational paintings where he could sum up his vision, simply and boldly. All extraneous tricks were eliminated, and in that important sense, these paintings became signifiers for his life’s body of work.

Although done late in his life, these paintings have the exuberance of youth, an aerodynamic sleekness, and the freedom and finesse that only an artist who had painted for 60 years could create. Like Titan, Matisse, and Bonnard, De Kooning only got better with age and was definitely “good to the last drop.”

s