This spring, the Jewish Museum is preoccupied with Israeli men. On the second floor of the Museum Mile institution, 14 large-scale canvases offer Kehinde Wiley’s insightful take on the subject, which manages to say something refreshingly meaningful about Israel. This might be in part because Wiley is not Jewish and has little to do with Israel.

To be sure, 35-year-old Wiley, a gay African-American painter, thrives on questions of identity, history, and social context, which he has fruitfully explored in depictions of young black men. His work integrates the here and now of their attitude and presentation with heavily referenced formalism that draws predominantly from Old Masters portraiture.

In more than a decade of success in his career — if not quite a star, he’s surpassed the milestone of sure promise — which took off after his graduation from Yale’s fine arts program in 2001, he quarried his models mainly from America’s black hip-hop jurisdictions. Several years ago, he went global, working in China, India, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Africa to begin his “World Stages” series.

In 2010, he set his eye on Israel, traveling there for one hectic month, studiously fishing for darker-skinned models. Ethiopian-born Jews, a community that migrated to Israel mostly in the 1980s and ‘90s, and Israeli Arabs fit the bill. The result, “The World Stages: Israel,” will be on view through July 29.

Unlike other Wiley works, which reference heavily European art history, his Israeli pictures mostly employ Jewish symbolism as the expressive, almost campy, background for the models. His graphic language faithfully follows concrete examples — mostly ceremonial papercut and textile pieces — dug up from the museum’s troves of Judaica. Cases containing the artifacts themselves are integrated into the show, nicely setting the tone for the portraits.

“The World Stages: Israel” merits attention for at least three reasons. The first has to do with Wiley and his commitment to the representation of men of color. This exhibition is far from a retrospective of his entire body of work, yet it demonstrates well his ability to explore sensitive social context and distill from its specificity and distractions the pure crux and central concerns of his work.

The second reason why the Wiley exhibition is interesting has to do with Wiley’s identity as a gay artist. His work suggests he is intrigued, though not consumed, by his sexuality, as if he were more interested in exploring it in a playful, rather than dead serious, way. Homoeroticism is at the core of some of his work — I’m thinking of his “Saint Sebastian” or his arousing, après Caravaggio, “Ecce Homo,” which features a black youth as likely the most muscular Jesus in art history — but in his Israeli line he rather plays down this theme; it is hinted at, even evident in some cases, but never constitutive. He offers us a wonderful inquiry into the tacit eros of straight-acting.

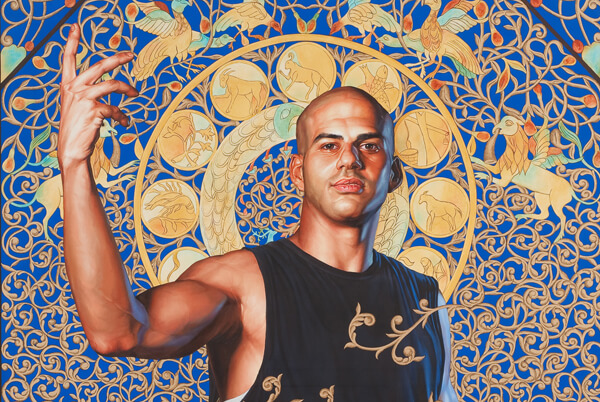

A case in point is the portrait of Roman emperor-like Leviathan Zodiac, my favorite in the exhibition. With stately posture, fair complexion, and dispassionate expression, authoritative Zodiac is effortlessly confident, transcending any sexual or private station. Nonetheless, his uplifted right arm slyly showcases the curve — and potential — in his bicep muscle, a detail that is surely erotic but not a bit sexualized.

Imperious Zodiac also suggests the third compelling feature of Wiley’s exhibition, which has to do with Israel itself. Looking at Zodiac, I can easily tell he is Israeli, but to get more specific is hard. Jewish or Arab? Ashkenazi or Sephardi? Observant or secular? Poor or rich? Even, gay or straight? The breaking down of identity is very much in the eyes of the beholder. On his very first visit to Israel, Wiley came remarkably close to realizing a Platonic image of the Israeli man.

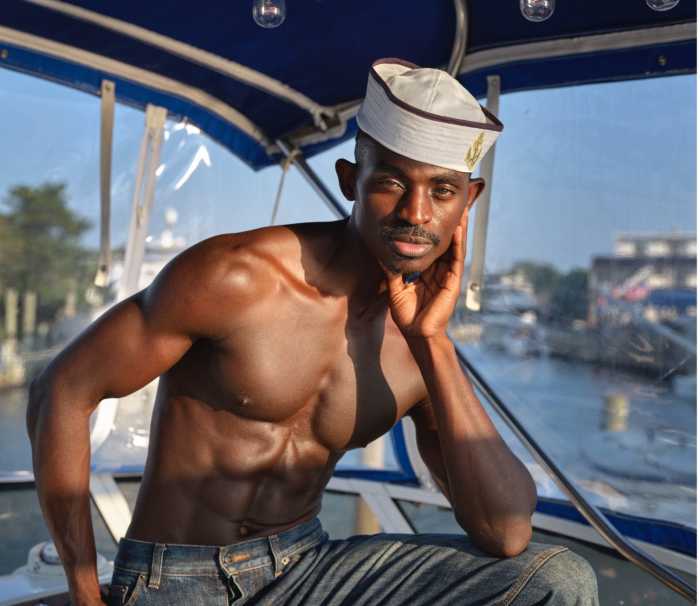

Generally, however, the more confident characters portrayed in the series — also the more likely to grab attention — are the Ethiopian Jews (about two third of the models), as if they were more suitable subjects for the signature empowerment Wiley brings to his work.

Yet, both groups he studied are distant from the upper echelons of Israeli society, so why are the Ethiopian Jews amenable in a way the Israeli Arabs are not?

As an outsider, Wiley is able to reflect rather than distort, capturing a telling nuance about Israel. Though both Ethiopians and Arabs are outside the Israeli mainstream, the Jews at least can envision inroads toward integration; in fact, they are even able to define themselves through their rejection of the pot in which they are to be melted.

Indeed, Wiley’s Israeli Ethiopian Jews share a rebellious air. Look at one of the exhibition highlights — the portrait of 26-year-old Kalkidan Mashasha dressed in an ostentatious uniform-like shirt loaded with memorabilia of deceased Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. Mashasha’s hip-hop lyrics and impressive biography star in the show’s catalogue and press materials; he even performed at the opening. How can we avoid adoring this could-be student and soldier who gave up a prestigious education and army experience for a career as a radical hip-hop artist? He’s an intelligent, caring, and charismatic man — for sure, deserving of our attention — who has forged a persona of an about-town fringe talent who takes pride in defying authority. What’s more Israeli than that?

Or consider “Alios Itzhak,” which, in a supersized mural emblazoned on a wall on East Houston Street has become the show’s poster boy. The museum acquired this oil and enamel canvas, which has a market value estimated by the New York Times at $130,000. Itzhak, cocky, straightens his back and daringly looks you in the eyes.

Showy gestures of this type are not found among the portraits of the Israeli Arabs, who seem more hesitant, reflective, questioning — to my eye, more Jewish than Israeli. What mainstream will they rebel against? What chance is it that the melting pot would make room for them?

A structural marker renders the nuanced differences between Jewish and Arab explicit. Each frame in the exhibition is topped with a small hand-made icon displaying a plaque. For the Jewish men, Wiley picked the iconic image of the Ten Commandments; for the Arab men, he used Rodney King’s famous question, “Can we all just get along?,” in Hebrew. The query reads apologetic and disempowering, particularly given that it is posed asymmetrically.

Free from political commitments to Israel and concerned instead with the representation of black men, Wiley effectively communicates the poverty of civic identity in Israel. Arab or Jewish, each man as a standalone offers a personal perspective on Israel. As an ensemble reflecting the nation, however, they do not cohere.

Essentials:

KEHINDE WILEY | “The World Stage: Israel” | The Jewish Museum | 1109 Fifth Ave. at 92nd St. | Through Jul. 29 | Fri.-Tue., 11 a.m.-5:45 p.m., Thu., 11 a.m.-8 p.m. | Admission is $12; $10, seniors; $7.50, students | thejewishmuseum.org

Yoav Sivan, an Israeli journalist who lives in New York, can be contacted via YoavSivan.com.