Innovative productions of classic operas brave some risks at the Met

Two divergent examples of modern stage direction were on view at the Metropolitan Opera earlier this month as the company unveiled new productions of “Don Giovanni” and “Salome.”

Of the two stagings, Marthe Keller’s take on “Don Giovanni” (seen March 20) represented the thoughtful, text-based school of production, with particularly strong emphasis on details of meaning in the recitatives. A striking example of this simplicity of effect was Thomas Hampson’s performance of Don Giovanni’s serenade “Deh vieni alla finestra.” The baritone gradually walked away from the window of his intended conquest, absorbed in his song, suggesting the character’s narcissism and self-absorption.

The traditionally flighty Donna Elvira (Christine Goerke) is played as a vulnerable but grimly determined survivor, the usually icy Donna Anna (Anja Harteros) as a woman on the verge. For once, Don Ottavio emerges as more than a cipher with two great arias; as directed by Keller, tenor Gregory Turay plays the young nobleman as a Hugh Grant-type, clearly bewildered, and rather embarrassed by Donna Anna’s mood swings.

After a rocky couple of seasons, Turay has happily returned to good form, but Goerke’s glamorous, vibrant voice fell short of pitch in softer moments. Conductor Gareth Morrell summoned a lush, romantic sound from the Met pit; his only misjudgment was the unsingably quick tempo for the first act finale.

Harteros is a glorious find, with a haunting dark vocal timbre and an innately elegant manner of phrasing. Even as the occasional high note spread or turned wiry, the soprano spun the long lines of “Non mi dir” into arches of inevitable-sounding beauty, with special elegance in the smorzando (dying away) endings of phrases.

The audience favorite was, rightly, Rene Pape as Leporello, a superstar performance in every sense of the word. The magnificence of the voice and musicianship of this bass is familiar, but what I enjoyed most of the entire evening was Pape’s witty imitation of the singing of his master (Hampson), all pear-shaped vowels and fussy rhythms. Hampson’s voice is nowadays rather threadbare in tone, and in emphatic passages he tends toward rant in lieu of a genuine forte. But he is alive to the text and the music every moment, creating a frighteningly real character, a sociopath all the more dangerous for his easy charm.

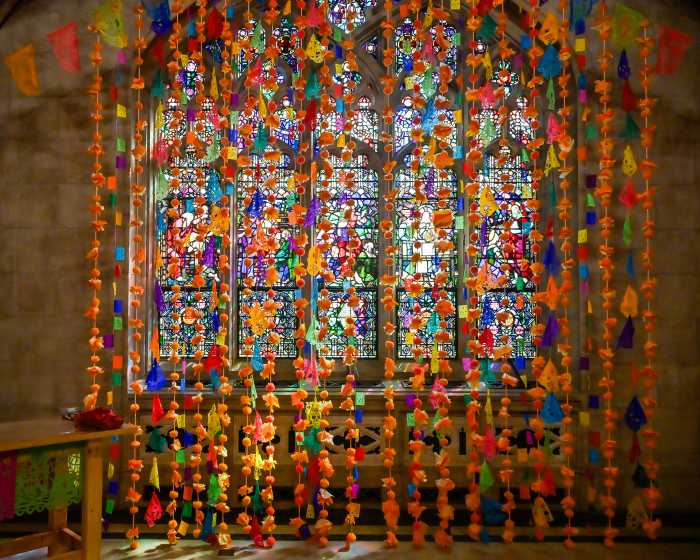

Serious thought about the text seemed the furthest thing from Jürgen Flimm’s mind in his production of “Salome” (March 19). The gaudy staging updates the action to an unfinished luxury hotel sometime around the middle of the 20th century. Salome swans about in a bias-cut silk evening gown, Jokanaan sports Che Guevara revolutionary uniform chic, and Herod’s banquet guests look like they wandered over from a pool party at Lana Turner’s.

Okay, fun is fun, but a far more serious problem here is Flimm’s notion that Salome (Karita Mattila) should be a champagne-sozzled celebutante (Paris Hilton on her way to becoming Courtney Love), blatantly and crudely aware of her sexuality from the start. Given what I consider a wildly wrong take on the character, I was bowled over by Mattila’s ferocious acting and aggressive singing of the score, attacking the high notes with frightening force. She is still relatively new to the role, so perhaps that explains a certain lack of imagination in her vocal interpretation, with little shading of dynamics and flabby rhythm. But even with these reservations, this was the sort of essential diva experience queens will be talking about decades from now.

The remaining artists in the opera boasted some of the finest voices on the Met roster, including Albert Dohmen (Jokanaan), Larissa Diadkova (Herodias), and Matthew Polenzani (Narraboth). Allan Glassman (jumping in for an ailing Siegfried Jerusalem) offered firm, virile tone. Doug Varone’s choreography for the celebrated “Dance of the Seven Veils” might pass muster in Suzanne Somers’ nightclub act.

The scandal of the night was the conducting of Valery Gergiev, with hair-raising lapses of coordination between pit and stage every couple of minutes. This is the sort of sloppiness that deserves to be booed, loudly and long.

At the New York City Opera, a disinterment of “Sweeney Todd” showed signs of life when Elaine Paige took the stage as Mrs. Lovett. The British musical theater diva boasts a thrilling belt range as well as powerful legit high notes, and she inhabits the character of the murderous pie maker as if it were written for her. Next to Ms. Paige, the rest of the cast seemed slow and clumsy, in particular Mark Delavan in the title role. His massive granite voice could not compensate for an utter lack of demonic personality.

James Jorden is the editor of parterre box, the queer opera zine (parterre.com)