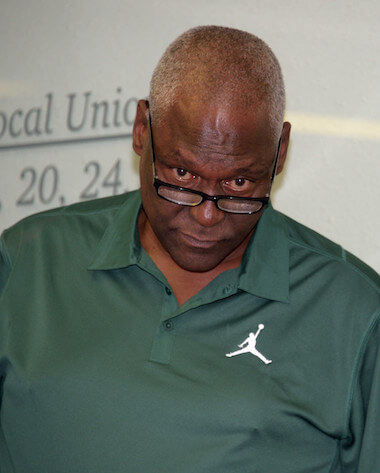

Governor Mario Cuomo after an HIV/ AIDS event at the World Trade Center. | DONNA ACETO

Former Governor Mario Cuomo, who died New Year’s Day at 82, was famously labeled “Hamlet on the Hudson” for his indecision about entering the presidential contests of 1988 and 1992, but it was the late Gay City News journalist Doug Ireland who first dubbed him Hamlet, even before his election as governor in 1982.

Cuomo’s long, drawn-out process in 1983 in issuing a simple gay rights executive order, promised during the previous year’s campaign, led a local gay newspaper, New York City News, to run his picture on the front page with the headline: “Cuomo Executive Order: To Be or Not to Be?”

When the order was finally issued, the paper’s headline was “Cuomo to Gays: I Did It My Way.” This reporter got a personal call from the governor to remonstrate about having raised doubts he would stay true to his pledge.

Outspoken against death penalty, hero from ’84 DNC keynote, Mario Cuomo cautious, uneven on gay, AIDS issues

Cuomo’s reputation as a liberal lion was based largely on his principled opposition to the death penalty and his stirring keynote address to the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco in defense of a government that cares.

But his political persona was also shaped in significant ways by who he was not — his long-time political rival, New York City Mayor Ed Koch, who was still fighting with him from the grave, labeling Cuomo a “prick” in a video released after his 2013 death. Koch’s resentment, which boiled for more than 35 years, was based on his firm belief Cuomo had allowed — and then never apologized for — posters in Queens in the 1977 mayoral runoff (that Koch won) that read “Vote for Cuomo, Not the Homo.”

That poster incident was the only gay or AIDS-related matter mentioned in the lengthy New York Times obit by out gay reporter Adam Nagourney. This article will focus on gay and AIDS issues, which played major roles in Cuomo’s tenure.

When Koch died, there was an outpouring of anger from many veteran gay and AIDS activists — as though a scab had been picked — condemning his inaction on AIDS and failure to get a city gay and lesbian rights bill passed for nine years despite promising to do it within six months of taking office in 1978.

While some of the gay and lesbian reviews of Cuomo’s record are mixed, there was no similar level of anger directed toward him during his life or after his death despite the fact that he also presided over the explosion of the AIDS plague as governor from 1983 — less than two years after the epidemic was first detected — through 1994, more than a year before protease inhibitors started saving people with AIDS from almost certain death.

At an ACT UP demonstration in Albany in 1988, the firebrand gay activist, writer, Vito Russo — who would die of AIDS just two years later — spoke and did not mention Cuomo. When Cuomo won a third term as governor in 1990, however, ACT UP so noisily disrupted his election night celebration that he never came down to the ballroom to claim victory.

“I can’t recall Cuomo as doing anything,” author, playwright, and longtime activist Larry Kramer said this week via email. “That’s why ACT UP went up to Albany en masse to protest him. He came out and said a lot of b.s. feel-goodies statements, but I don’t recall any of them as coming true. Was the [New York State] AIDS Institute his doing? I guess they were useful. But considering that his state was among the worst struck down with HIV/ AIDS, he was not a compassionate leader.”

Kramer, an unbending critic of Koch, nonetheless argued, “Cuomo seemed content to let Koch be the total fall guy for this one. Again, compare this reaction to how every leader and media outlet are publicizing Ebola almost since its appearance. If we’d had that kind of non-stop attention, we’d have a cure by now.”

Noreen Connell, former president of NOW-NYS, recalled her group’s battle to speed legal redress for people living with AIDS before it was too late. NOW, she said, “sued him because it was taking 10 years for finding a ‘probable cause’ for complaints filed with the Division for Human Rights. By this time, most AIDS complainants had died and those claiming employment discrimination had their back pay awards set aside by the court. Talked liberal, acted conservative.”

New York’s gay press skepticism about Cuomo’s plan to issue a promised nondiscrimination executive order is met by the governor’s personal retort.

But Cuomo, who spent most of his time in Albany, was not as near a target as Koch for activist wrath. The governor also had credible gay activists in his administration, including the former head of what was then the National Gay Task Force, Virginia Apuzzo, who was well-respected and connected to a nationwide network of gay and progressive political activists. Koch’s gay liaison was the reactionary Herb Rickman who distrusted and often attacked the activist community — and literally procured men for the closeted mayor. (Rickman, who died in October, was the unpleasant Hiram Keebler character in Kramer’s “The Normal Heart.”)

Still, Koch fulfilled a pledge to issue a gay rights executive order on the first day of his administration in 1978. Cuomo issued his order in late 1983 — 11 months into his term — angering even his closest gay allies with the delay as well as the directive’s content, which was viewed as weak. The governor refused to impose the gay rights protections on contractors doing business with the state, as activists had demanded.

Before even meeting with gay leaders about the order, Cuomo held one with right-wing religious leaders opposed it. At a press conference, Cuomo defended his delay on this basis, saying “this was a subject that should have a lot of discussion.” He “had meetings with the gays and anti-gays, and the clergy for and clergy against,” the governor explained.

Political scientist Kenneth Sherrill, in 1977 the first out gay person elected to public office in New York as a Democratic district leader, wrote to Cuomo during the executive order controversy.

“Dear Mario,” the letter read. “I was distressed to read… that you met with a bunch of religious bigots and assured them you would do less to protect the rights of lesbians and gay men than Mayor Koch.”

Koch supporters had warned him, Sherrill told Cuomo, that by backing him over the mayor in the 1982 Democratic primary for governor, “I would have to deal with a vindictive Mayor. It never dawned on me that I would also have to deal with an immoral Governor.”

When the order came out, veteran gay activist Allen Roskoff, who worked for the administration as assistant vice president at the state’s Urban Development Corporation, said he got a call from Andrew Cuomo asking what he really thought of it.

“I told him it is extremely weak, terrible,” Roskoff said. “He said, ‘I’m going to have the Jewish press call you for comment.’ They called me. I repeated the assessment. My boss called me in and said, ‘How dare you insult the governor’s order.’ I said, ‘Andrew wanted me to!’”

Roskoff said there would have been no Cuomo promise of an executive order in the first place if the Village Independent Democrats had not met with Cuomo the day of their endorsement vote and stood firm in demanding it as a condition for giving him their nod.

“He said he doesn’t make such commitments, so they said fine — no endorsement,” Roskoff said. Cuomo gave in.

Mario Cuomo, during his 1982 run for governor, with Allen Roskoff, Betty Santoro, Bella Abzug, Ermanno Stingo, and Andy Humm. All but Abzug, a former member of Congress, were affiliated with the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights. | STEVE ZIFFER

In the ‘77 mayoral race, Koch, the Greenwich Village “bachelor” congressman, publicly courted the gay vote. While Cuomo also supported banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, he was viewed as the more socially conservative, outer-borough Catholic candidate, in the public eye largely for having mediated a housing dispute in Forest Hills that scaled back the number of low-income units planned for the middle class neighborhood.

In his memoir, “Mayor,” Koch wrote that during that campaign, “it became clear that people around Cuomo were going to stoop to an attack alleging I was homosexual” using “undercover attacks” and “it was clear that Mario was going to be doing nothing toward disciplining or dismissing” those who participated in what he called “the smear.”

Koch wrote that even though they both endorsed gay rights legislation, Cuomo decided it would be “politically advantageous… to portray me as someone who favored what he called ‘proselytization’: the teaching in schools of homosexuality by homosexuals.” Koch wrote that he also got wind of a Cuomo effort to get a “renegade cop” to “perjure himself” and say he had “arrested me for soliciting male prostitutes in the street.”

Koch, of course, was homosexual and used former Miss America Bess Myerson — who died at 90 on December 14 — as his consort during the campaign, marching hand-in-hand in parades to ward off the talk of his being gay.

Though Koch took immediate action on his gay rights executive order, he made a hard turn to the right in his early months in office, alienating progressive activists and giving Cuomo valuable allies in his battle with the mayor for the ’82 gubernatorial nomination. Early in that primary year, Koch enjoyed poll leads of 30 to 50 points, so Cuomo’s victory was celebrated as a surprising rebuke to the mayor’s new-found style of racial polarization. Cuomo became a beacon of hope for liberals nationwide.

But as he himself said, “You campaign in poetry and govern in prose.” In addition to not delivering on the gay rights executive order in a timely or complete fashion, Cuomo never used his clout to get the state gay and lesbian rights bill passed. He also was content with having a State Senate controlled by Republicans, never lifting a finger to help elect Democratic senators as Governors David Paterson and Elliot Spitzer would later. (Mario’s son, Governor Andrew Cuomo, undermined a Democratic majority elected in 2012 by blessing a rogue Independent Democratic Caucus led by Bronx Senator Jeff Klein that caucused with Republicans to keep the party that won at the ballot box from controlling the chamber.)

As a Jesse Jackson candidate to the 1984 Democratic Convention, I was in the hall for Cuomo’s dramatic keynote. If delegates had the power, they would have nominated him by acclamation that night over the bland Walter Mondale. That said, Cuomo could not bring himself to directly mention gay people in that speech, saying only, “We embrace men and women of every color, every creed, every orientation, every economic class,” omitting “sexual” before orientation so as not to scare the horses and hoping it would be enough of a signal to LGBT voters to suffice.

The other memorable speech in San Francisco that week came from Jackson, and he did refer directly to gay and lesbian people.

Ginny Apuzzo was offered a job as gay/ lesbian liaison in the Cuomo administration, but told them she would “do that for nothing. I wanted a job that makes me a colleague.” In 1985, she was appointed first deputy commissioner of the Consumer Protection Board, “a fabulous place to work on AIDS.” She went on to become deputy commissioner of housing and the first openly gay or lesbian person confirmed by the State Senate when she was named to head the Civil Service Commission.

On Apuzzo’s first day on the job with Cuomo, she recalled in an email, “there was a banner headline in the Albany Times-Union and a pic of me with ‘LESBIAN EX-NUN WINS TOP JOB.’ I get called to the governor’s office. He said, ‘Sit down. You don’t get more press than your boss!’ I said, ‘It’s a terrible headline.’ He said, ‘It’s a good headline. It says “WINS.” It could have said “LESBIAN EX-NUN STEALS TOP JOB” or “HUSTLES TOP JOB’!”’”

Apuzzo attributed her close working relationship with Cuomo to two things: “One is I’m Italian. The other is that while a lot of people got into government and then came out of the closet and then took roles in the gay and lesbian community, I came with an activist background and connections to our communities around the country… I could give the governor not just an emotional reason for doing something, but the legal footing and the comparison with other states.”

Apuzzo offered a starkly different assessment of Cuomo’s record on the AIDS epidemic than Kramer.

“Our AIDS policy was arguably the best in the nation,” she said, something she attributes to “the core of leadership we had in New York State and relationships with leadership in California and around the country. We brought the entire administration together, demanded an interagency task force on AIDS, and ultimately the governor supported the AIDS Institute and had budget hearings bringing in agency heads” to get them to say what they were doing about the epidemic. “We got partner benefits at the end of the administration. I think Mario Cuomo understood the biggest public health crisis of our time,” Apuzzo added.

Apuzzo used her clout to bring Cuomo commissioners to “Breakfast Club” meetings with gay and lesbian leaders, something that helped smooth over Cuomo’s 1986 lieutenant governor pick — upstate Congressman Stan Lundine, who called himself a “flaming moderate” and had twice voted for the infamous McDonald Amendment that denied gay people with discrimination claims access to the Legal Services Corporation, a non-profit organization authorized by Congress.

Apuzzo was able to bring Lundine around on gay issues.

Veteran activist John Magisano said of Cuomo, “He was truly a mixed bag in terms of leadership.” The governor, he noted in an email, appointed “unprecedented numbers of gays and lesbians (including me),” and “founded the AIDS Institute and oversaw some of the first HIV/ AIDS-specific supportive housing.” He also credited Cuomo with creating “the Crisis Prevention Unit (where I worked for four years) within the Division of Human Rights to respond to bias crime since the Senate would never take up a hate crimes bill because it listed sexual orientation as a protected class.”

Still, Magisano concluded, “He had to be pushed every step of the way and push we did.”

Another veteran gay activist, George De Stefano, who worked at the AIDS Institute under Cuomo, said, “The relationship between the Institute and the administration was at times strained, sometimes worse than that. The director, Nick Rango, was a pretty radical physician… who encouraged representatives of affected communities to advocate and protest. He even created a funding stream that basically supported community organizing and advocacy. He hired some ACT UP members and encouraged them to keep the heat on.”

According to De Stefano, the governor seemed to be okay with that.

“I give Cuomo credit for not obstructing what Rango tried to do,” he said, though he agreed the governor had to be pushed, particularly on “funding issues.”

Governor Andrew Cuomo plays basketball during the 1994 Gay Games with hate crimes bill activist Howie Katz (l.) and Senator David Paterson, the leader of hate crimes efforts in the Legislature who himself went on to become governor. | COURTESY: HOWIE KATZ

Coming up on his 1986 re-election battle, Cuomo grabbed some headlines on the issue of public sex, with a call to shutter gay bathhouses and, according to a 1985 Daily News story, “to limit sexual activity in bars that allow ‘aggressively promiscuous’ sex, possibly through an education campaign.” Through Health Commissioner Dr. David Axelrod, the governor got the Public Health Council to ban “dangerous sex” in certain “establishments.” The definition of “dangerous sex” was “anal intercourse and/ or fellatio,” which vastly inflated the risk of oral sex while leaving out vaginal sex — which could signal to women they had less to worry about in the epidemic. The Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights sued Cuomo and Axelrod over the discriminatory guidelines, a case not settled until 1994 — when the Council added vaginal sex to its definition of “dangerous” behaviors.

In 1987, the racially motivated killing of Michael Griffith in Howard Beach led to a push for hate crimes legislation in New York State. Veteran Queens gay organizer Ed Sedarbaum, who stepped up to lead in shepherding communities in support of such a measure, wrote on Facebook this week that Cuomo “was always able to provide profound quotes for us. But in the end I came to feel that, like many Democratic Assembly members, he preferred to have the Senate reject it so he could campaign on how hard the Dems fight for minorities.”

Gay activist Howie Katz, who chaired the Hate Crimes Bill Coalition and led a 1992 march from New York City to Albany to push for it, said, “The Republican Senate majority told Mario in the late ‘80s they would pass it if they took out sexual orientation and Mario went to Senator David Paterson and Assembly Member Roger Green of the Black and Puerto Rican Caucus and they refused the deal.”

Katz said he forged a bond with Cuomo after inviting him to play basketball with his team in an exhibition at the Gay Games in New York in 1994. Katz was hopeful the access he gained in that way would help the push for the measure that year, but the Senate remained resistant through Cuomo’s defeat at the hands of George Pataki that November. Another six years would pass before the bill became law under Pataki and a Republican Senate in 2000.

Gay rights legislation also failed to get a vote in the State Senate during Cuomo’s years in Albany. Until 1986, much of the frustration in the community focused on Koch’s failure to exert clout to win a sexual orientation nondiscrimination law in the city, and that took much of the heat off of Cuomo since few expected Albany to act first. Again, it was Republican Pataki and a GOP Senate that moved on a gay rights law in 2002.

Cuomo, in his post-Albany years, became more outspoken on LGBT issues, eventually supporting same-sex marriage — an issue he deflected when asked about it in his losing 1994 race. According to Roskoff, Cuomo was “very proud of his son” when the current governor won marriage equality in 2011.

“I feel privileged to have worked with him and am proud of the quality of the man,” Apuzzo said this week. “He had qualities sorely lacking in politicians today — a strong moral commitment to right and an immense amount of compassion. I really love this man.”