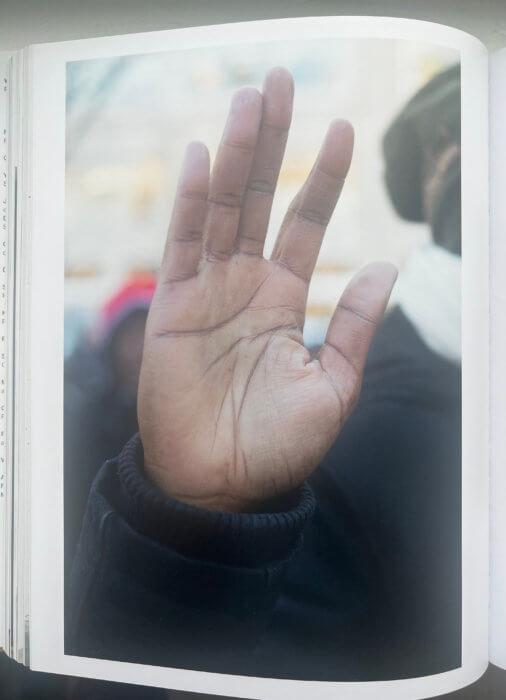

From his portraits of Public Enemy front man Chuck D. in the US to dancehall music mavericks Patra and Shabba Ranks in Jamaica, to Londoner DJ Smokin’ Jo, to capturing from overhead two young, Black, presumably male bodies locked in a pretzel-like embrace on the ground, to his exhibition touring across the African continent, to his collaboration, musical and photographic, with Frank Ocean, to peas boiling in a pot in his East London flat while a Pentecostal preacher wails in the background, to the tunes he spun in Berlin’s Panorama Bar, to the close-up of a human palm with melanated creases he photographed raised in “Hands up, Don’t shoot” protest in Union Square, to many other images and ventures, the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, born 54 years ago in the city of Remscheid, Germany, has over his 35-year professional career consistently engaged in a significant way with what some might consider odd for someone of his positioning in the world: the Sign of Blackness.

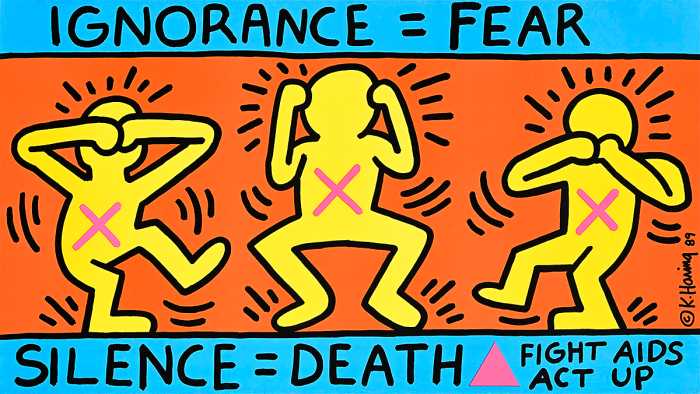

Be it in aesthetics, in culture, in history or in sociology, Tillmans has looked without fear — or, perhaps, a helpful dose of it to facilitate learning and growth — at bodies, cultures, and struggles in the Black diaspora. Tillmans just wrapped up the “Last Look” of his first major museum retrospective in the United States, “To look without fear” at the Museum of Modern Art. Gay City News contributor Nicholas Boston presents an edited transcript of an interview he conducted with Wolfgang Tillmans on the eve of the exhibition’s opening on Sept. 12, 2022. This is a retrospective of the retrospective.

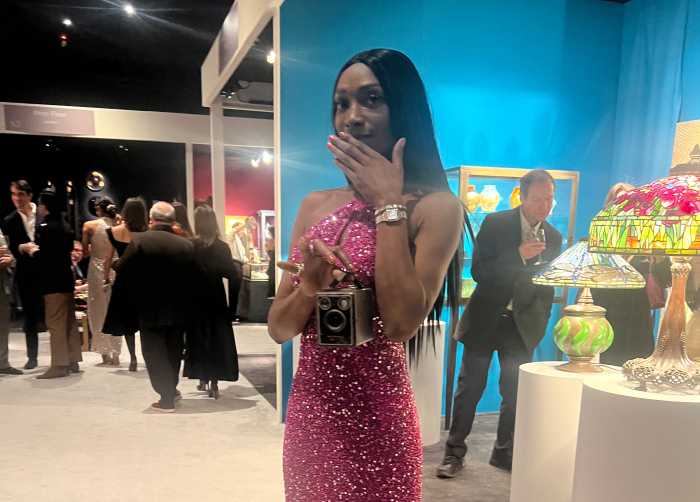

“Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear,” the 320-page hardcover exhibition catalogue, edited by exhibition curator Roxana Marcoci, is available at MoMA Design Store.

Wolfgang Tillmans: I’m just very overwhelmed by the reactions and how people are touched by the exhibition, how different moments in the works intersect with their lives. The exhibition feels to me very free and I feel like I didn’t compromise. It translates a sense of freedom that I wanted to communicate, a sense of openness and ongoing-ness and multiple points of entry.

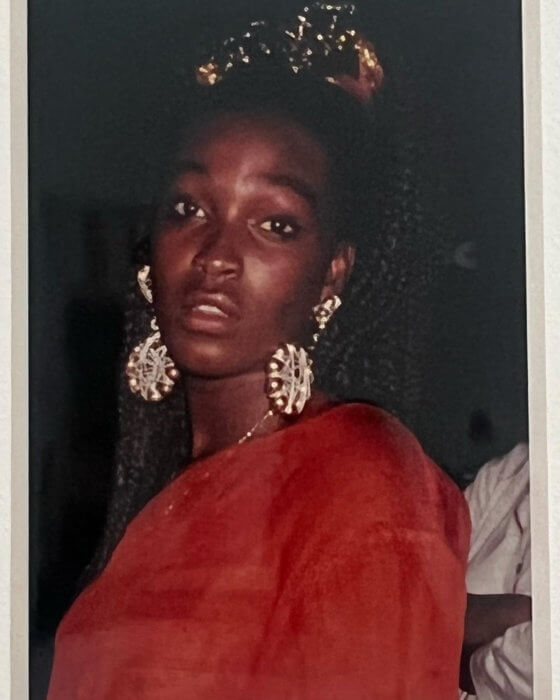

Nicholas Boston: On that point, I want to take you back to the photographs that you took of Patra and the dancehall scene in Jamaica at a time when there was a lot of discussion around homophobia in Jamaican dancehall music. You captured a moment, immersed in that context as a European gay man. What was that moment about for you? What took you there? Maybe you could speak a little bit about that generally.

WT: I was working for i-D magazine as a generator of portraits. I was bringing stories to them, but also taking assignments. I was open to be confronted by scenes of people that I had little connection to, and there was this opportunity to go to Kingston, Jamaica, to photograph Shabba Ranks. I was on the borderline between, “Should I enable a rabid homophobe or create these images?”

NB: Obviously, it was a significant moment in your career because you selected that work — or that work was selected — to be in your retrospective.

WT: The photograph of the dancehall scene of the man and woman dancing [Ragga Dancer, Kingston, 1992] has a universalness, their grinding. I don’t always photograph nightlife, but, it does touch me as something so fundamentally human: a desire to be together, to get lost in the night, to feel our bodies differently. I am seeking that experience myself in the first place.

NB: I feel like I saw you photographing in The Cock [the New York nightclub], the original one, on Avenue A, in the late ’90s, early 2,000s. What was that experience of New York at that time like for you?

WT: Electroclash times. [Laugh] I think that was an exciting time. After 2003, I was a lot less in New York, for about 10 years. And, I guess that’s also when a lot of the nightlife moved out of Manhattan. I was lucky enough to have lived here in the early ‘90s when I could still experience the Meatpacking District, The Lure, and so on.

NB: You’ve just given me a thought here. Do you think that after a moment has happened it should remain a memory? What is your opinion of relaunches? I’m thinking now about BUTT magazine. You were so central to establishing the aesthetic of that enterprise. It defined a scene in the early 2000s and now it has been relaunched after going out of print for 10 years. What do you think of that?

WT: I mean, Gert [Jonkers] and Jop [van Bennekom] are two of the smartest people in publishing and in design and they were smart enough to know when it was time to stop publishing BUTT. They stopped a successful operation because they stopped to ask themselves, “Why are we continuing this?” I think it was a fair question. And, then, 10 years or so later … I was part of a conversation group, old and new faces, discussing, “How would we do BUTT now if we wanted to do it?” In the end, I was so busy with everything that I didn’t contribute to the first issue. But, I must say I found that they did a great job. And I am excited and happy to be in the second issue. It is a contemporary mix and the diversity that’s there does not feel artificially handpicked or inserted. I have a wonderful short interview with Matthew Blaise, a gay/queer activist in Lagos, Nigeria, and a photo essay on Juan Pablo Echeverri, Colombian artist and friend of mine who, so shockingly, surprisingly died this June of malaria.

NB: It’s interesting that you mentioned that in the upcoming issue, you’re in conversation with this Nigerian activist and creator because it seems to me that you have through your career, if you look at the work that you’ve done, if you look at the collaborations that you’ve had, if you look at the music that you’ve created, there are so many access points to Blackness. You’ve had a consistent engagement with Blackness and Black people and Black cultural production over these past 35 years. Would you say that’s correct or not?

WT: I mean it is correct in the way that it is an ongoing development. You call it an “engagement,” but I see it more as an awareness, an awareness of Blackness and the specificities of the origins of where we all are now. Like, I had an African cities tour that I ran from 2018 till this spring: eight exhibitions in eight countries. Each and every country on the African continent was formerly colonized, except for Ethiopia, and even they were touched by colonialism and how Europe left their imprint. So, it was important for me to experience and exhibit in contemporary Africa. Also, being a longtime New Yorker, even though I only lived here permanently for two years…

NB: And you own a place on Fire Island that you come to regularly.

WT: Yes. As a longtime New Yorker and also as a European with a sense of social safety that we consider normal in Europe, it has always been striking to me to see how disproportionate homelessness hits Black people in America, or, and, shocking to me how unaware America had been until 2014 [the start of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Zimmerman’s murder of Trayvon Martin] when people learned the term “systemic racism” — like not the overt kind of racism, but all of what is deeply ingrained in the different ways society works.

I myself had this strong realization in 2014, thinking like, wow, this country really is coming to terms with itself on this issue for the first time in a long time, a couple of generations have not thought about this seriously. ‘Cause, you know, in Europe, people always were in disbelief that Michael Jackson was the first Black artist on MTV because for us so much of American popular music was Black music. [Laugh]. It’s like, yeah, yeah, yeah. Not. And, of course, every European country has its own huge package of dealing with racism and so on. But, I strongly felt it then, in 2014, that people started to realize that this country is built on a racist history, on genocide of the original population, and then the crime of slavery and the crime of not doing something to bring full equality after its abolition. But, anyway, I felt really hopeful and thought, “Wow, this is really moving something now.”

Then, two years later, 2016, you had the backlash of the 50% percent of American voters that did not feel that anything should change, that any of these topics should be raised. As a gay person, I sometimes feel sorry that there’s so much equality and awareness for gender and sexuality, which is alright, but not for race. There is such an aversion, like an allergy, in some people to discussing race. [Laugh]. Think about critical race theory. I mean, what is the problem with thinking about what went on in this country for 200, 300 years now? What is the problem with thinking that our great-, great-, great-grandfathers maybe did this or that?

NB: Coming back to the exhibition, there’s a wonderful portrait with a kind of blue wash of a man of African descent looking at the camera. Could you talk a bit about that portrait?

WT: It’s titled, “Remy at Spectrum” [2015]. So, after 10 years where I was less in New York and less infatuated or fascinated with this city’s nightlife, I started coming back in 2013, 2014, and I discovered The Spectrum, in Williamsburg, that safe space, safe house, for anything queer. I sort of walked visibly with a camera, a small one. And, at one point I caught his eye. It was with just the slightest wink of an eyelid that he gave me permission to continue. So I took a couple of pictures of him and, then we exchanged a few words and, and it turned out that he knew who I was. So that was, uh, lucky. [Laugh]

NB: That partly also accounted for the wink of the eye because he recognized you and he invited you. He was like, “It’s Wolfgang Tillmans, I have to!” I mean, if I’d see you, I would wink and hope that you would take my photograph. I want to talk about your video piece of the peas boiling with the voice of the preacher in the background. Was it just that he was on the TV in the background?

WT: No, not TV. This was in 2003 in my London studio in the East End, Bethnal Green, and across the road there was a Pentecostal African church, like “Built on the Rock” church. [Laugh]. At the time, I had no connection to Africa, where these churches come from, but, of course, now having traveled — Cameroon, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria — I know the importance of these African, um, of, of these churches in particular. And, of course, also about the homophobia that they continue and spread in Africa. But, so I was, on a Sunday afternoon at lunchtime, boiling peas in my kitchen and had the windows open and I observed the dancing peas in the pot. I felt actually, you know, I have to photograph this. It is so, fascinating how directly they react to the heat of the gas turning up and down. And, um, and I started filming and had the, the microphone on the camera running and, and realized that there’s this enormous noise coming over across the street from the preacher, shouting, “Repent! Repent!”

NB: One final thing: What does the title of the exhibition mean? I mean, what does it mean to you?

WT: It comes from me encouraging people to use their eyes without fear, to look without fear, to use your eyes freely, to turn things upside down, to invert them. Your mind can do a lot. And it’s free, free of charge. You can definitely subvert everything with your eyes. You can attribute value to whatever you think is valuable, and attribute beauty to whatever you feel is beautiful.

Nicholas Boston is Associate Professor of Journalism and Media Studies at Lehman College of the City University of New York.