Arnie Zane’s post-Stonewall, pre-Calvin photos celebrate the body’s commercial insouciance

It is a bitingly cold day in New York City, eight days into the new year. At dusk, New Yorkers dash past each other on the streets, bundled to their necks, bound for the warmth of home.

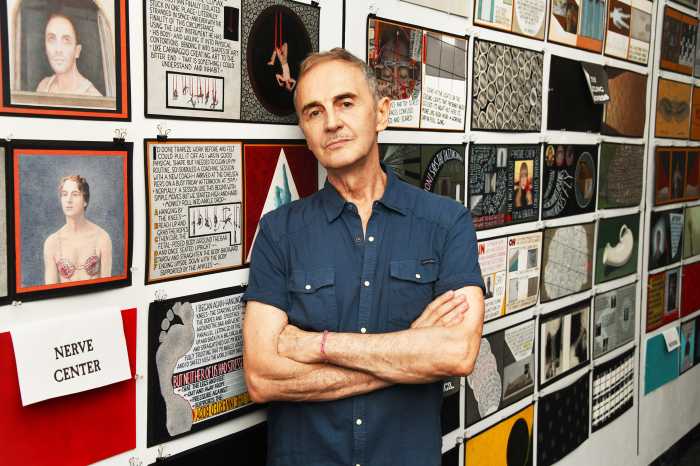

In the halls of the Paula Cooper Gallery in West Chelsea, a small, dedicated group listens as Bill T. Jones the dance master and artistic director of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, explains the series of photographs, some taken 30 years ago, by Zane, his deceased partner and co-founder of their eponymous dance company.

Jones moves from image to image, relating, as only he can, the back story behind the work. The talk is personal, yet not sentimental—until Jones reaches a collection of three self-portraits of Zane in swimming trunks at a beach. Two of the shots are close up and cropped at the chin and mid-thigh; the third is taken from a greater distance, showing Zane’s face. “Those of you who love somebody dearly,” Jones says to the crowd, drawing in close to the portrait of the man for whom he still dances, “you know the exact typography of their body.” He turns to the photograph. “This triangle right here,” he says, motioning in a soft gesture at the hair on Zane’s chest. “This is maybe the thing that I miss the most.”

The exhibition “Arnie Zane: Photographs” has the quality of something once lost, now found. It exudes this feeling for several reasons. First, because it comes as a surprise to many that Zane (1948-1988), known the world over as an innovative performer, actually started out with strong aspirations of being a photographer, including a 1973 fellowship during which he produced some of the photographs on exhibit.

Second, because not until 1999 were the photographs assembled and shown publicly in “Continuous Replay: The Photographs of Arnie Zane” at the UCR/California Museum of Photography in Riverside, California. (The Paula Cooper show is in fact the first of Zane’s work to be mounted in New York since the photographer-dancer’s death from AIDS.)

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, with Jones’ and Zane’s company celebrating its twentieth anniversary season, entitled, fittingly, “Evoking a Phantom,” one cannot help but call Zane to mind.

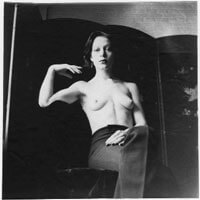

The exhibit is a striking remembrance of things past. “On the Hill in Johnson City” (1972) describes Zane and Jones, just into their 20s, playing at something that looks like a circus act. There are other hand-tinted photographs of the toned young lovers, taken during the couple’s brief sojourn in Amsterdam. There is the shirtless, white body of a street thug Zane paid to photograph. And there is the nude study Zane made of Pearl Pease (1975), a destitute, mentally ill geriatric patient he took in. This last set of portraits is disturbing, not because it chronicles the body in decline from age, but because it reminds us of the bodily ravages Zane would succumb to a decade later. “Arnie was thinking about the body, about the flesh, for a long, long time,” says Jones.

Many of the photographs celebrate Jones’s own body, although he says they were not meant to be flattering shots. And indeed, considering what was to come later in the 80s and 90s from photographers inspired by the male body, these studies by Zane are not particularly arousing.

Jones recalls what one reviewer said of Zane’s partially clad self-portraits: “An old geezer in his underwear.”

And here is the real message of these photographs, beyond the tragedy of loss, the pre-celebrity status of the artist, interracial fascination, or whatever else one wants to glean about the history of gay aesthetics from them. Regarding Zane’s confident stare at the camera, he clearly had zero self-consciousness about his flat chest, the excess fat around his midsection, the unintentionally feminine cut and fit of his bathing shorts.

These photographs describe a pre-Bruce Weber, pre-Calvin Klein era, one before gay men took the irreversible plunge into gym-built body worship.

We also publish: