Lorraine Hansberry’s classic more focused on the women this time

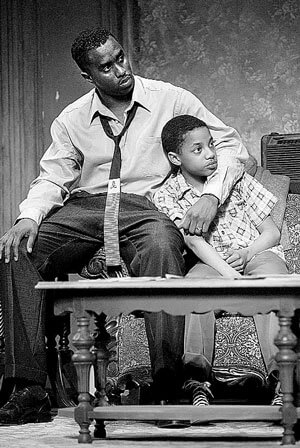

Sean Combs may be the biggest marquee name in the current revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” but his performance, while generally solid, never really ignites, leaving the heavy lifting of this heartfelt play to the other members of the cast.

Fortunately, they are more than equal to the challenge.

By virtue of his celebrity, Combs is the biggest news of the production, and by adding “actor on Broadway,” to his list of credits he is both diversifying his publicity machine and bringing a new and diverse audience into the theater, just as Madonna did in her similarly sufficient acting debut in “Speed the Plow” many years ago. The publicity is important, and without Combs’ name attached, it’s likely the revival would not have happened on so grand a scale.

Happily, Combs’ performance isn’t as bad as the early buzz would have had us believe, nor, however, does it fulfill the role as written, by a long shot. He is best in the broad middle ground of the character, portraying the “every day” elements of Walter Lee Younger, where he is a foil to the women in his life, where he turns on significant charm. Where the performance fails is in believably tapping into the anger, despair, and disappointment of the character, most notably in the second act breakdown in which we need to see Walter Lee impersonate through rage the stereotyped servile Negro behavior of the 1950s. It should, particularly today, be a shocking moment, but it falls flat.

Without that catharsis, Walter Lee never emerges as an individual but remains a follower, under the thumb of wife, sister, and mother. If Walter Lee becomes irrelevant, a major piece of the play—the dynamic between men and women in the world Hansberry portrays—is lost. Director Kenny Leon, who does a fine job with the rest of the production, has had to work around Combs’ limitations too obviously, leaving him with his head in his hands and his back to the audience at what should be critical moments in Walter Lee’s experience. Audiences deserve a great deal more from this character than Combs seems able to deliver.

The play takes its title from a Langston Hughes poem, and is on many levels, a meditation on the poem’s opening line: “What happens to a dream deferred?” The story concerns the Younger family, who share a tenement apartment in Chicago. As the play opens, they are about to receive $10,000 in insurance money from the death of the father of the family. Walter Lee wants the money to invest in a liquor store. His sister Beneatha wants the money to pay for medical school. The mother, Lena, wants to buy a house and move out, and Walter Lee’s wife, Ruth, supports that move. Walter Lee is a chauffer and Lena and Ruth are domestic workers—all of them barely getting by—so the money is a promise of change and a new kind of economic freedom they have never known, a realization of the dreams that never before seemed attainable.

Ruth takes part of the money and buys a home in a white section of town. She gives the rest to Walter Lee who promises not to put it into the liquor store, only to do so anyway and have a partner run off with it. But the family sticks to their plan to move, determined to make a go of it, despite the efforts of the homeowner’s organization in their new neighborhood to buy the house and dissuade them from integrating their community. It is Lena, the matriarch, who makes the decision that no matter the hardships, the dream of their own home is one that they will not defer—and in making that choice a new world of possibility is opened for all the characters.

Because Combs never seems more than a charming dreamer, the dynamic of this production shifts to the women. Because the women’s characters are so well developed, the result is extraordinarily moving. Phylicia Rashad plays Lena with a kind of richness that is consistently remarkable. Even the slightest moment is fully developed in her performance. Lena is the most grounded of all the characters and becomes the center of the all the action, almost unwittingly, as her decision about what to do with the money drives both Lee Walter and Beneatha.

Audra McDonald gives an achingly lyrical and understated performance as Ruth. She is the heir apparent to Lena’s role as matriarch, and though it is a burden she often wishes she didn’t bear, McDonald plays the part with a quiet acceptance that makes her riveting. At one point, contemplating taking a bath in the new house, we see, in an imagined moment, that the pain and weight of the years can be lifted. Ruth’s dreams are not big in the way that Walter Lee’s or Beneatha’s are, but she matches them in her intensity. McDonald makes the role completely believable throughout and conveys the passion that Combs never musters.

As Beneatha, Sanaa Lathan is marvelous. She is skittish and fickle, not ready to take on the matriarch role, even in training, and not sure who she is. In her search for an identity, we see Beneatha torn between the African student, Asagai, and George, the rich middle class boy from her college. At one point, Beneatha dresses in African garb for a date with George—a symbol of how she is struggling to locate herself as a young black woman in her world. Lathan is particularly good in the relationship with Combs as they bicker back and forth as brother and sister.

The play, with sets by Thomas Lunch, costumes by Paul Tazewell, and lights by Brain MacDevitt, conveys an overall sense of barely trapped energy straining to burst its seams. The happy ending is not complete, but grasping hold of even a flawed dream with full hearts and great hope makes this production work quite well on balance.