Polly Bergen only safe haven from train wreck Mark Hamill helps create

There is some wonderful news for theatergoers coming out of the Belasco where the new play “Six Dance Lessons in Six Weeks” has just taken up residence. They can rejoice, confident that no matter what they see this season, they will not see a worse show than this turgid, insufferable, and deeply offensive play.

Playwright, to use the term as loosely as it could ever be construed, Richard Alfieri’s pandering swill belongs to that hideous school of God-awful theater that includes such bombs as “Bermuda Avenue Triangle,” “Queen’s Boulevard,” “Things You Don’t Say After Midnight,” and “If You Ever Leave I’m Going with You.” The common thread in all these show is that they deal in shallow stereotypes and make comedy out of presumably safe targets—in this case old women and gays.

Through plot manipulation, false emotion, stock characters, and tired laugh lines, Mr. Alfieri takes subject matter that should be at worst boring and relatively harmless––imagine “The Golden Girls: The Lost Episodes”–– and spins it into something that approaches a bias crime.

Mr. Alfieri posits that older women are lonely, bitter, and forgotten. Gay men, on the other hand, are lonely, bitter and trying to forget the scars of their sorry lives in which love has eluded them. These are not merely offensive—and dated—stereotypes, they also make for boring characters. Can a playwright, not to mention the people that funded this debacle, be so out of touch with contemporary sensibilities that they think this is funny? Would they find plays appropriate that took as their theme that all Jews are cheap or that African Americans are endearingly servile?

The same device that makes Jackie Mason one of the most consistently loathsome entertainers living today, playing to the assumed prejudices of his niche audience to get easy laughs at the expense of others, is at work here. As my father used to say to my brothers and me when we engaged in inappropriate humor: “’Tain’t funny, McGee.”

But, if you can get past the political atrocities of this play, you’ll discover that underneath it all, the writing is really, really… awful. It’s predictable and insultingly condescending. You’ve heard of foreshadowing, that delicate literary technique through which one gets an inkling of what’s coming up? Mr. Alfieri uses what can only be called fore-broadcasting, as if he were yelling, “Guess what happens next!” It gets old. Truly, Dr. Seuss tells better, and more sophisticated, stories.

Mr. Alfieri’s story, such as it is, concerns a lonely elderly woman, Lily, and the relationship that ensues with Michael, a dance instructor, who comes to her house to give her, you guessed it, six dance lessons in six weeks. The play is structured around each lesson, and at the performance I attended, you could hear the audience counting down to the end. “Only four to go.” “Only two to go,” and so forth, which should give you an idea of how tedious this whole thing is. For some reason that could only make sense to Mr. Alfieri, Lily and Michael start out insulting one another and fighting. Gosh, it must be all that pent up loneliness that automatically bonds old queens and old dames, even if their emotions can only find suitable expression in insulting a stranger.

Repellent as the scenes of Michael and Lily bickering are, they are nowhere near as nauseating as when the two finally develop a kind of mother/son relationship and find the love and acceptance in each other they can’t find anywhere else, or are afraid to. Michael is going to accept that he’s gay and maybe he can love again.

There are also a series of stirring developments––really superficial attempts to go for the heartstrings of the audience––each of which has the exact opposite effect, making one want to go for the playwright’s throat. The old bat downstairs, who Lily has been barraging with insulting phone calls, dies and when her son turns up, he is–– mirabile dictu––gay! Lily herself, in remission from cancer in lessons one through five, has a recurrence around the time of lesson six.

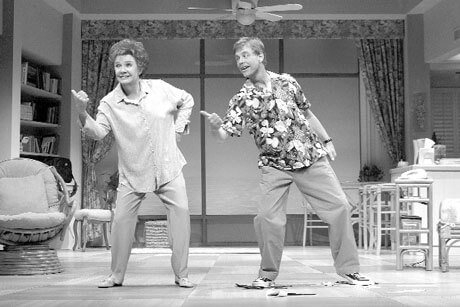

Happily, there is a bright spot––Polly Bergen in the role of Lily. Without her, I wager that two-thirds of the audience would have walked out at the intermission. Ms. Bergen is a radiant performer who, against all odds, gives this play whatever redeeming value it has. She deserves a much better showcase for her lively talent, precise timing, and splendid comedy. Though the script tries to cut her off at the knees at every pass, she somehow manages to rise above it. Besides Ms. Bergen, the only thing that really works is the set by Roy Christopher. He has captured the prefab sterility of a St. Petersburg condo with eerie accuracy.

Speaking of eerie, Ms. Bergen’s co-star Mark Hamill is a walking train wreck. His performance is strident and overly mannered, a kind of antediluvian image of a homosexual who is shallow, shrill, and shamelessly artificial. It is as empty a performance as you could ever see, highlighted by those popular fag signifiers, the limp wrists and swaying walk. All the talk in the script about not judging people seems like quasi-liberal cant imposed on a truly hateful, arcane image of what it means to be gay. Mr. Hamill is too loud in every respect, and any moment of sincerity seems false. Whatever force he may have drawn on in other roles, none of it is evident here.

Of course, Mr. Hamill’s performance may be the responsibility of director Arthur Allan Seidelman. Mr. Seidelman’s evident ineptness radiates through the piece in the characterizations, the awkwardness of the relationship between the characters, and the long (though blessedly restful) blackouts in between each scene.

Happily, this hideous experience is now all in my past. And having gotten through it, let me say that nothing, not even the comforting knowledge that you won’t see anything worse for a long time, should tempt you to get anywhere near this half-baked turkey.