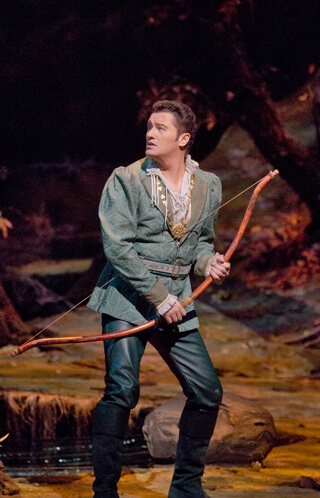

Nathan Gunn and Sasha Cooke in the San Francisco Opera world premiere of Mark Adamo’s “The Gospel of Mary Magdalene.” | HENRY FAIR

Happy Supreme Court news mightily energized San Francisco Pride, already glowing from Frameline’s Film Festival and Shangri-La weather. All that and opera, too!

San Francisco Opera under David Gockley fosters new work. Last month, it hosted the world premiere of “The Gospel of Mary Magdalene” by Mark Adamo, the popularity of whose genial “Little Women” (1998) has not extended to 2005’s sit-com “Lysistrata.” Where that Gulf War-era project ran from controversy, the new piece surely courts it in its intriguing and well-researched basic premise: the centrality of Magdalene to the story of Jesus — here, “Yeshua” — and the erasure and distortion of that by the traditional Gospels. Archdioceses will surely fulminate against Adamo’s libretto, which raises pertinent questions about Christianity’s foundation and biases.

Other political issues, however — including marriage rights and the legality of circumcision — arise as lame one-liners. The disciple Peter, disapproving of Magdalene and of female participation in Yeshua’s work, Adamo finds wanting for privileging political organizing and anti-imperialist revolt over self-actualization and coupled love, reminding one how he drained “Lysistrata” of anti-war content, leaving only romance at its core. Is Adamo’s a quietist philosophy?

An opera dispatch from San Francisco’s Pride Week

The premise’s genuinely interesting aspects — for example, the tensions illegitimacy engendered between Yeshua and his mother (here “Miriam”) — needed language less self-consciously repetitive, prolix, and tending to doggerel. There were countless monosyllabic words yielding too many internal rhymes and creating an unfortunate “New Age greeting card” vibe. Kevin Newbury’s fluid direction minimized the piece’s gaucheries and longuers, but some cuts might help.

Musically, there are manifest debts to Britten — echoes of “Grimes,” “Screw,” and “Dream” — and, more than any other opera I can recall, Sondheim, whose word-setting Adamo referenced in a program note, as well as lots of pseudo-Bernstein (the harmonies kept seeming to lead into “There’s a Place for Us”). Admirably, Adamo does achieve singable lines and piquant harmonies. If not original — nothing in the score would have been novel in 1950, certainly not the use of radio voices — the idiom flows pleasantly enough. The orchestration, often diverting, shows marked improvement from “Lysistrata.”

June 25’s third show offered some very fine singing. Mezzo Sasha Cooke (Magdalene), for whom Adamo has composed before, looked and sounded lustrous and committed. Nathan Gunn’s sincerely played Yeshua juddered at climaxes, sometimes shading flat. One sensed the music needed the bigger, “all-American” sound of a Lawrence Tibbett.

William Burden’s Peter showcased incredibly beautiful tenor singing encompassing crystalline diction and expressive fervor. Maria Kanyova — a passionate Miriam, rather sparsely heard from — boasted a strong top, which could both soar aloft and shine in pianissimo. Lower down, however, phrases tended to vanish. Bass James Creswell made a resonant Pharisee, and Daniel Curran (tenor) and Brian Leerhuber (baritone) projected keenly the well-written parts — suggesting models in Monteverdi, Berlioz, and Mussorgsky — of two soldiers providing commentary.

Locally debuting Michael Christie led the orchestra expertly. The full chorus — often saddled with Adamo’s direst platitudes musically and verbally — lacked perfect ensemble.

“Les contes d’Hoffmann” two nights later was a Laurent Pelly co-staging with Barcelona and Lyon. Though sensitively conducted by Patrick Fournillier and an interesting — if ultimately not altogether successful, in terms of dramatic pacing — use of much more responsibly-sourced musical materials than this textual “problem” work often receives, the evening stayed pretty flat and disappointing. It was neither amusing nor moving for much of its considerable length.

This partly resulted from Chantal Thomas’ deliberately banal, nearly empty shifting sets inspired by the work of an obscure Belgian symbolist, Léon Spillaert. We were left with little atmosphere, save in the Antonia act, where Pelly brought in dry ice and Dali-like spinning wheels as well as placing longtime collaborator Natalie Dessay in as vocally flattering positions vis-à-vis her colleagues as humanly possible. Dessay phrased with distinction and had very touching real moments dramatically, but — with flutter and spreading under any pressure whatsoever and a high C sharp almost out of reach — is clearly wise to be retiring from active operatic duty, though one wishes she’d still attempt Poulenc’s “Voix humaine.”

Otherwise, the only truly international-class performances were Matthew Polenzani’s sensitively acted, beautiful limned Hoffmann — gorgeous sound at low dynamic levels, but fine line throughout, even though this part’s demanding stretches take this savvy singer right to the limit of his tonal resources — and Munich-based mezzo Angela Brower (Nicklausse/ Muse), who contributed lovely singing and the evening’s few emotionally resonant moments.

The rest — Christian Van Horn’s solid, competent villains, Hye Jung Lee’s wildly applauded but not really remarkable Olympia, and the attractive if somewhat generic-sounding Irene Roberts (Giulietta) and Jacqueline Piccolino (Stella) — evoked sound “regional” casting. Dessay aside, Thomas Glenn’s Spalanzani showed the best French.

“Cosi fan tutte” on July 1 suffered from skittish, overly fussy direction by Jose Maria Condemi, who littered the prettily designed stage — a Monte Carlo casino in 1914… whatever — with distracting extras, and Nicola Luisotti’s rather episodic conducting. The excessive continuo work and wannabe-hip surtitles also proved skittish and overly fussy. Two of the cast were Massively Unnecessary Imports: Marco Vinco’s unpleasantly hammy, shouty Alfonso, providing only idiomatic Italian, and Christel Loetzsch’s metallic, grainy Dorabella, a pure liability vocally. Susanna Biller sang decently but was directed to embody the Ur-Despina, hands on hips and raffishly charmless.

The evening’s pleasures lay in the remaining trio: Ellie Dehn’s sincere Fiordiligi, showing beautiful sound and musicianship throughout; young Philippe Sly’s movie-handsome Guglielmo, with terrific legato singing; and ardent Sicilian tenor Francesco Demuro, evoking the young Pavarotti in Ferrando’s challenging music.

A perfect concert for Pride Day: massively out conductor Michael Tilson Thomas leading the Symphony in the first-ever concert “West Side Story” — one of a series of four from which a composite CD will appear on the SFS’ own label. We heard Bernstein’s 1984 revised score, with no Arthur Laurents dialogue — just the few lines written by Sondheim. Having a top-flight orchestra romp through this score was thrilling. The snare drum and brass section won deserved roars of applause.

Tony was Pride Day grand marshal Cheyenne Jackson, a very good though unmagical singer with excellent dynamic control except at the top, which tends to blare. The words might have been caressed more, which also held true for Alexandra Silber’s uneven Maria. Silber’s decidedly appealing flute-like quality hit instability crossing the high passaggio, and in Act Two someone dialed her mic up to distorting levels. One hopes another show went better for her.

Sexy and utterly confident vocally and dramatically, Jessica Vosk simply cleaned up as Anita, and there were strong, dark-voiced alpha males aboard with Kevin Vortmann (Riff, much better sung then usual) and Kelly Markgraf (Bernardo). “Somewhere” — premiered on Broadway by future opera star Reri Grist — found a lovely, soulful yet straightforward interpreter in the superb Julia Bullock. An inspiriting afternoon.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.