ILLUSTRATION BY MICHAEL SHIREY.

When as many as 9,000 athletes gather in Cleveland August 9-16 for Gay Games 9 (GG9), at least one New Yorker will be able to say he’s seen it all.

Charlie Carson, 59, attended the very first Gay Games in San Francisco in 1982. Since then, he’s returned to San Francisco and also competed in New York, Chicago, Vancouver, Amsterdam, Cologne, and Sydney.

Carson was one of less than two-dozen New York athletes who traveled to San Francisco in 1982, including one other swimmer and a diver, among 125 in total who competed in aquatics. It was a very good start for his Gay Games career. He came away with six medals — including three golds and two silvers.

Four years later, 300 New Yorkers traveled to San Francisco. In total, 400 swimmers competed in the Games — 18 of them from New York but the lion’s share Californians. That year, Carson medaled but picked up no gold.

His career in competitive swimming is emblematic of the explosion in the Games and in opportunities for organized LGBT sports generally. When Carson attended the first two Games in San Francisco, he and his fellow New York swimmers were freelancers of sorts. In 1987, swimmers, divers, and water polo players from different cities formed International Gay & Lesbian Aquatics (IGLA). Two years later, New York had enough swimmers to form Team New York Aquatics to compete in the US Masters Swimming (USMS) as an official club.

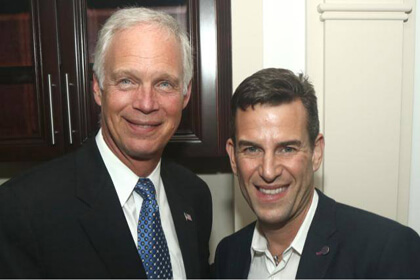

Charlie Carson chats with one of his Team New York Aquatics swimmers. | JASON ANDREW

Carson first heard about the Gay Games via word of mouth. In 1981, he joined the New York City Gay Men’s Chorus, during that organization’s earliest days getting off the ground. The chorus was, he said, the first gay group he ever joined. It was from one of his fellow singers that Carson learned about the Games planned for San Francisco the following year.

“I didn’t know what to expect but I had never been to San Francisco,” he recalled, “so I figured even if the Games weren’t that good, at least I’d get a visit to San Francisco out of it.”

Carson’s doubts proved unfounded.

“It turned out to be fantastic,” he said. “It jump-started this network of contacts — people who before that had given up the idea of competing in sports as adults.”

Carson soon showed himself to be a joiner, an organizer, and a leader. Based on meeting other New York athletes at the ’82 Games, “I began to compile lists,” he said. After helping to launch TNYA in 1987, he oversaw the aquatics competition at the 1994 Games in New York, which coincided with the city’s mammoth celebration of the Stonewall Riots’ 25th anniversary. Carson has also been involved in building an international swimming organization that hosts competitive LGBT events in each of the three years when the Gay Games are not held. He has promised himself that this year will be his final one as a member of the board of the Federation of Gay Games.

As he became well-known in the LGBT sports world, Carson also took on other athletic pursuits. As a way of keeping himself in shape for his swimming, in 1982 he joined Front Runners New York, an organization of running enthusiasts started in 1979. He remained active in FRNY for 17 years, though something had to give so he could keep juggling his growing sports responsibilities. By 1986, Carson left the Gay Men’s Chorus and has not sung in any group since. When he leaves the Gay Games board next year, he hopes to rejoin the singers he left behind nearly 30 years ago.

LGBT swimmers in New York no longer have to depend on fortuitous conversations with those in the know to learn about organized competition, Carson said. The youngest swimmers in TNYA, he said, for the most part learned about the group on the Internet. TNYA membership now tops 500, competing in swimming, diving, and water polo. The group will send roughly 70 swimmers to Cleveland, and 15 water polo players from New York are also expected to participate.

With so many members, the group has exploded beyond the confines of its original practice space at John Jay College on the West Side and now holds workouts, as well, at the Dwight School on the Upper West Side, Baruch College on the East Side, the Chinatown Y, Hostos Community College in the Bronx, and Long Island University in Brooklyn.

If big-time professional sports are getting their first taste of out gay competitors with Jason Collins now playing on the Brooklyn Nets and Michael Sam expected to be a top pick in this year’s NFL draft, the rise of organized gay athletics clued in the amateur sports world some time ago.

“We have Olympic medalists who will swim with us,” Carson said. “We have really changed the world in this way.”

When Carson participated in the 2013 off-year international swimming competition in Seattle, he was at the high end of his five-year age bracket and came home with no gold medals. Because he turns 60 in this calendar year, he will be kicked up into the next age bracket in Cleveland this summer. Being the kid in the competition again, he harbors hopes for some gold.

“It’s silly how important that seems,” Carson said, in a tone that made clear there is nothing unserious at all about his plans for August.

Jeff Kagan, founder of the New York City Gay Hockey Association, has been a key organizer in the local LGBT sports scene for the past 15 years.

Anyone who has participated in the LGBT sports world in New York for any amount of time has probably met Jeff Kagan. Fifteen years ago, he founded the New York City Gay Hockey Association.

By that time, he was already playing in the city’s adult division amateur hockey league, which competes at Chelsea Piers, on a team called the Ugly Americans. More than half the Uglies, it turned out, were gay, something not known to all of the team’s players. Kagan and a few other gay players decided to call a team meeting after one of their games so that those who wanted to could come out.

“We sat there and made the announcement,” he recalled, “and everyone said, “Okay,” and then we showered.”

Based on the interest he saw among gay hockey players for organized competition, Kagan pushed to organize the Gay Hockey Association. Its teams originally played only amongst themselves, but in a league with just a few teams and varying degrees of skill across them, the opportunities for spirited contests were limited. Today, the gay teams, half of whose members, Kagan guessed, might in fact be straight, play against each other and versus the other teams who compete at Chelsea Piers.

Hockey is by no means the only sport that has engaged Kagan over the years. After the successful launch of the Hockey Association, friends of his who played basketball asked for his help in starting a league of their own. He figured he’d lend a hand — and ended up serving as the league’s commissioner for several years. Perhaps stubborn about learning from his mistakes, Kagan recently helped start a gay bowling league.

Kagan has also been instrumental in a variety of efforts aimed at coordinating activities among the city’s mushrooming number of LGBT sports groups. For several years, Balls, Boards, and Blades was a periodic sports social aimed at addressing a problem the new leagues were encountering — the tendency of too many teammates to hook up with each other.

“The idea was ‘not with your teammates,’” Kagan recalled with a laugh. “Treat your teammates like brothers. Hook up with guys from other sports.”

Kagan was also one of a number of athletes who helped organize an annual LGBT Sports Ball in New York.

As New York’s LGBT athletics scene grew and individual leagues expanded, organizing events across all the sports became more than anyone realistically had time for. That doesn’t mean Kagan isn’t still pitching in. Today, he is the board president of Out of Bounds New York, an umbrella group that coordinates activities among more than 40 sports groups and also works to encourage acceptance of LGBT participation in team and individual competition.

Fundraising to sustain individual sports organizations is left up to each league, but Out of Bounds will raise the roughly $4,000 to pay for Team New York uniforms that the city’s athletes will wear in the Opening and Closing Ceremonies at the Cleveland Games.

Kagan explained that Out of Bounds’ work in promoting acceptance of LGBT athletes has led the group to join forces with the You Can Play Project, a non-profit effort that has actively sought high school, college, and professional teams’ endorsement of inclusionary policies. In January, You Can Play announced that every team in the National Hockey League has now been represented by a member speaking out on behalf of LGBT participation in sports.

Reflecting on the new moment in sports that the NHL’s posture and the emergence of Collins and Sam represent, Kagan said, “Once upon a time, I thought within five years there will an out gay player in pro sports, no question. Now that it’s five years, I’m amazed.”

Having participated in past Gay Games, Kagan, who is 45, will head out to Cleveland come August. This year, however, there’s a difference. During the past year, he’s gotten married and moved from Manhattan back to his hometown in New Jersey — and the time he once dutifully devoted to hockey has suffered. He readily conceded he’s more out of shape than is customary, but he also bragged that he’s lured his new husband onto the ice. The couple will compete together in Cleveland, though at a less competitive level than Kagan has in the past.

“I don’t play hockey for the competition,” he said. “I do it for the love of the game, the grace of the game.” Then perhaps concerned that his meaning had been misunderstood, Kagan added, “Though I do enjoy competing.”

A gold medalist in cycling at the 2010 Gay Games in Cologne, Dieter Klemke gives an un-dislocated thumbs up.

One athlete who doesn’t hedge in the slightest about his view of taking on his rivals is Dieter Klemke.

“I am very competitive,” he said flatly, flashing a sly smile and offering a small laugh, when asked to explain his love of cycling.

A native of Hanover, Germany who came to New York 28 years ago, Klemke, who is 46, entered his first Gay Games competition in Cologne in 2010 and won a gold medal in the criterium, a 12-lap, 17-mile race on a closed rectangular course that places a high premium on technique. In winning, he bested a field of 40 cyclists.

Klemke has not always been a serious cyclist. He took up the sport only seven years ago as he faced his 40th birthday.

“I needed to do something meaningful,” he explained.

As child, he was a competitive swimmer — “I fell in the water when I was five,” he said. He gave up the sport, however, when he was 16 after discovering “cigarettes and girls.” It was later — in 1994, when he was enthralled by the spectacle of the Gay Games and the Stonewall 25 celebration in New York — that he gave up girls and came out.

In the years after those Games, he briefly toyed with competitive bodybuilding, but found both the diet and the discipline daunting. For three consecutive years starting the year he turned 40, Klemke, who is 6-foot-4 and weighs about 235 pounds, did the San Francisco-Los Angeles AIDS Ride, experiences that sold him on cycling.

Around the same time, he helped found Out Cycling, one of the city’s two LGBT bike clubs. The Fast & Fabulous Cycling Club is the older and larger of the two, but while Klemke readily acknowledged that it has some of New York’s strongest LGBT cyclists, it also focuses a greater share of its efforts on recreational and social biking. Out Cycling, Klemke explained, is more focused on competitive events. It is also predominantly a male club, while Fast & Fabulous draws more evenly from across the community.

Explaining that he has no “winter gear,” Klemke said, “I ride in warm weather.” That doesn’t mean that his skills have gone dormant in recent months. Twice a week — increasing to three times a week this month — Klemke trains at Endurance Werx on West 37th Street, “pedaling against the computer” for 60 minutes.

During the spring, club members will do training rides of 35, 60, and 100 miles, some of the most challenging of them crossing the George Washington Bridge and proceeding up the Hudson overlooking its west bank. And in June and July, those cyclists headed for the Cleveland Games will be in Central Park every weekday morning to train.

“Everything you hate you learn to love,” Klemke said about what he can promise any new Out Cycling member.

One thing any athlete hates is injury, but when that misfortune befell him it was not in competition but rather while simply tooling around Manhattan. Hit several years ago by another cyclist, who was at fault, Klemke was thrown over his handlebars — to which he clung, dislocating both thumbs — and passed out briefly when he hit the ground. The offender fled before he came to, so there was nobody to send the bill for a very expensive replacement bike to. Klemke did get back up on the proverbial horse, however, once his thumbs had healed.

As he talked about the challenges of keeping a 100-member club organized and establishing a training routine for the half-dozen Out Cycling members going to the Games, it was clear that Klemke is in fact the “goal-oriented” sportsman he sees himself as. Still, for all his emphasis on a love of competition, he is motivated as well by the camaraderie cycling offers.

“I am very social,” he said. “I love challenging myself and training. And helping others in training.”

In nearly three decades since first arriving in New York, it’s apparent that the ’94 Gay Games, even though he was not yet competing, represented a high point for him. He also attended the Games when they were held in Chicago and in Amsterdam, and recalled the friends he made, from Australia and New Zealand in particular, in the Olympic Village in Cologne four years ago.

The six cyclists heading to Cleveland plan to rent a van, which will bring the cost of their week at the Games down to about $1,600 each, hotel included. Klemke urged other New Yorkers to seriously consider making the trip, athlete or not.

“If you’re even a little bit interested in sports, go,” he advised. “And you can participate. Remember, you don’t have to qualify.”

Then acknowledging that some New Yorkers might turn their nose up at spending a summer week in the industrial Midwest, Klemke said that with nearly 10,000 athletes and another 15,000 spectators, the Games are a defining gay event under any circumstance.

“Even if it’s in Cleveland,” he said. “We have to present. Out and proud, you know.”

And again, that sly smile.

For more information about Out of Bounds and the New York area’s LGBT sports leagues, visit oobnyc.org. For complete information about the August 9-16 Gay Games 9 in Cleveland, visit gg9cle.com.

Editor's note: The original print and online version of this story included errors, made by the writer, regarding statistics from the 1982 and 1986 Gay Games and the formation of Team New York Aquatics, which have been corrected above.