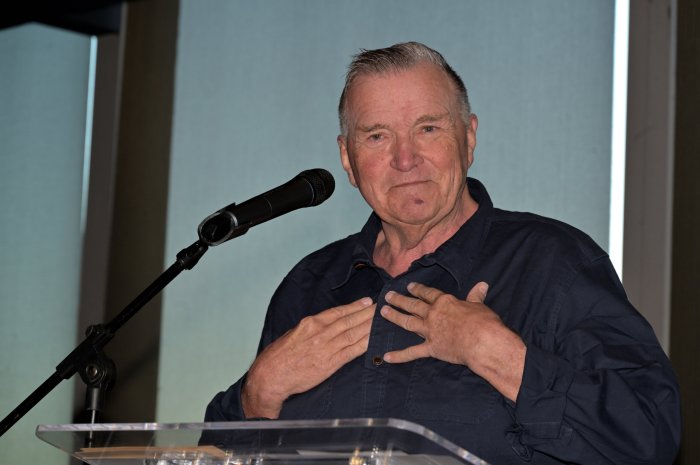

Mahmoud Hassino in Istanbul last year.

BY MICHAEL LUONGO | Mahmoud Hassino is a 37-year-old gay Syrian journalist, currently living in Turkey, who manages to frequently return to his homeland to record the uprising against President Bashar Hafez al-Assad. I originally became familiar with Hassino through his Syrian gay travel website, mazaj75.blogspot.com, and met him in person in Damascus in early 2010 during my book tour for the Arabic version of “Gay Travels in the Muslim World,” At the time, he was working for a culture magazine.

Gay City News’ decision to use Hassino’s name and photograph was made at his insistence, an effort to prove his bona fides after the scandal last about Tom MacMaster’s phony blog, A Gay Girl in Damascus (damascusgaygirl.blogspot.com).

“Everyone used that blog to discredit anyone who blogged or talked about homosexuality in Syria, and in the Middle East in general,” Hassino explained. “This is why I thought that coming out now is vital for the cause.”

He recently launched started a Syrian gay newsmagazine, Mawaleh (Arabic for nuts), which is online at issuu.com/mahmoudhassino/docs/mawaleh000.

Gay City News recently interviewed Hassino in a series of telephone and email conversations.

MICHAEL LUONGO: Tell us how you left Syria and what is going on now.

MAHMOUD HASSINO: I look at what is happening in Syria now as an uprising, which turned into an armed rebellion and then into a warlike uprising. Whilst mainstream media in the West call it a “civil war,” Syrians don’t feel it is a war of that kind. At the beginning of the uprising, I went on demonstrations, then started working on mobilizing people around me. I also worked with a group of Christians and Alawites [a Shia Muslim minority of which Assad is a member] and gays and lesbians aiming at mobilizing minorities. Even though that mission was a failure, I still think we did the right thing. It was dangerous, as regime control was at its peak.

I left Syria October 2011. Shortly after I arrived [in Turkey], the armed rebellion started, which was a shock to me since my friends and I do not believe in armed resistance. After I came to Turkey, I wanted to find my way, and I decided that I want to be a journalist, not an activist. I didn’t want to get involved and lose objectivity. I am anti-Assad, but what interests me in the revolution are the untold stories of people. I want to help telling these stories.

ML: As long as gays did not organize politically, gays were allowed to socialize under Assad. You and I even went to the weekly gay Damascus parties and to a gay-friendly bar downtown, and there were several cruising areas. However, in late 2010, there was a crackdown. Was this to please Islamists?

MH: Homosexuals are the easiest target anywhere and at any given time. What happened in Syria in 2010 was because the new head of the Criminal Investigation Security Branch, as it is called officially, wanted to show he was worthy of that post. No one would defend homosexuals in the Middle East, especially under the totalitarian regimes that existed back then. Of course Islamists would be happy if homosexuals were attacked, but so would the religious Christians. In 2010, priests in Tartus forced some families to try to cure their gay sons. The crackdown on gays is not a matter of flirting with Islamists as much as picking an easy target.

ML: Long before the uprising, you had trouble?

MH: I have been somewhat out since 2006. This caused me some problems with the authorities on several occasions, but nothing materialized to be a big enough threat for me to leave. It was mainly police harassment and intimidation, or perhaps a kind of warning not to ask for gay rights or write about them.

A park near the Four Seasons Hotel where gays gathered to cruise as recently 2010. | MICHAEL LUONGO

ML: Once the uprising started, government TV accused revolutionaries of being gay.

MH: It was the regime’s lowest point before the armed revolution started. Again, because homosexuals are the easiest target, which all Syrians would agree with, the regime started a homophobic campaign to say that the revolution is immoral because people who own the news channels, which are supporting it, are homosexuals. They went further by saying that everyone who is active in the revolution is gay — i.e., “sinners, immoral, and want to damage the fabric and the structure of the conservative Syrian community,” according to Ali Shueibi, who was the one behind the campaign. He used the word “luti” [sodomite].

Gays, Christians, Sunnis, Alawites, and others, might be pro-regime or anti-regime. My friends come from different backgrounds — Christians, Sunnis, Alawites, Ismaelis, Kurds, Assyrians, Circassians, etc. Most of them are anti-regime. Four of our contributors in the magazine are Christians, and three of them are anti-regime. People are entitled to their opinions. I only have a problem with those who support the killings and injustice.

ML: Syria is going from a secular country to a religious one. Many articles on rebels point to a religious zeal.

MH: Syria was not ever secular. Secularism in Syria was yet another regime propaganda. People were appointed in governmental posts in accordance to their ethnicities and religious groups. As for now, mainstream media like to focus on the few “religious and extremists” that are there, in a way to try to have a public disapproval of any kind of help or intervention in Syria. They focus on this to divert people attention from the main story — the Assad regime bombing, shelling, and killing civilians.

The things I see are alarming. There was a house where a family had made us breakfast, and it had been randomly shelled. There were body parts on the wall. You could still smell the blood. We met them for an hour, and they were all killed. It’s devastating you’re watching your own people being maimed and killed by the government. Eighty to 100 people are killed every day. Up until now, a broader sectarian conflict can be avoided, but something must be done. These children and these women didn’t do anything, and they were rocketed. I was furious with the world for letting this happen.

ML: Tell us about the queer Syrian magazine in Arabic that you have launched.

MH: The original thought I had was a series of awareness videos about homosexuality. A few months ago, I was contacted by some gay Syrians, and I found out that they are highly educated and that they write well. I also felt that they are proud homosexuals, so I suggested the idea of a queer magazine. They were excited about it, and we started discussing their safety since they are in Syria. I sent them the scripts I wrote for the video and my ideas of how to use the same concept in a magazine.

ML: What are your worries about the LGBT community in Syria as the uprising continues?

MH: I have personally witnessed the fallouts of the gay killings in Iraq. Many gay Iraqis fled to Syria to seek asylum and resettlement in Western countries. [At one point, more than 9,000 gay Iraqi men were exiled in Damascus.] Homosexuals are the easiest target in the Middle East, and I don’t want what happened in Iraq to happen in Syria, even though I still feel it is unlikely that the situation in Syria will go that far. However, I do believe that homosexuals will be targeted no matter who wins the war in Syria. It is important to start raising awareness and call for a “united gay front” in the country.

There is nothing more worrying to a homosexual than extremists. I go to rebel-controlled areas in Syria and meet with “fighters with long beards,” an image that is connected to extremism and terrorism in the West and everywhere else in the world. However, I have never felt threatened by those long-bearded fighters. “In Syria, we are moderate. I grow my beard because the regime and his thugs hate it” — this is what almost everyone told me, but this doesn’t mean I am not worried about the future.

All religions, if given the power, will be dangerous to gay rights. In the Middle East, religion feeds the traditions, and vice versa. I do believe that the return of the gay presence in central Damascus will not be easy even if secularism wins over Islamism. Our biggest problem is the traditions. Our most important target is social acceptance. That needs a long time. We have hard work ahead of us, no matter who wins this fight over power in Syria.