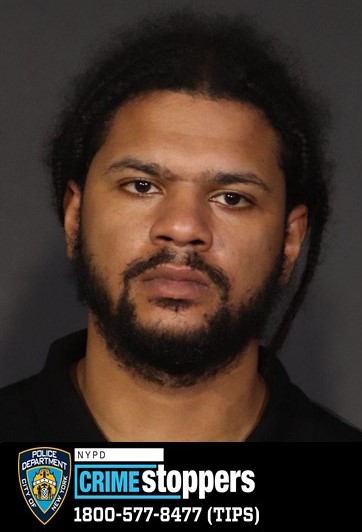

Venice Brown, Terrain Dandridge, Patreese Johnson, and Renata Hill are four young women whose lives were turned upside by a four-minute episode of violence outside the IFC Center in August 2006. | LYRIC CABRA

BY SETH J. BOOKEY | Many LGBT Americans have seen things and met people the average American never encounters, but even within the community we have a lot to learn from each other. A great documentary will help viewers dig below the deep-held truths that comfort them, and at this year’s Human Rights Watch Film Festival, there are rewarding opportunities to look for right in our own backyard.

Whether it’s a Navy SEAL who came out, in a big way, as transgender, four girls from the hardscrabble streets of Newark, or a nationally known gay celebrity, there are parallels: they survived personal and social traumas and are willing to discuss their private pain in a public way, on film.

At a pride event years ago, I met a transgender woman who told me she couldn’t see her children or grandchildren because of “what I am.” Her words struck me with dread at being “what,” not “who.” Her attitude seemed like self-deprecation, but surely for too many in society — even in the gay and lesbian community — dehumanizing transgender people comes all too easily. That may, in part, be due to ignorance, from not really getting to know folks in the trans community.

Human Rights Watch Film Festivals LGBT offerings challenge our own assumptions

One good first step in remedying this — in about 80 minutes — is to watch “Lady Valor: The Kristin Beck Story.” Not a primer on transgender issues, but a highly personal look at a former Navy SEAL with 21 years experience and many medals and commendations who is much happier now that she can live as a woman.

Directors Sandrine Orabona and Mark Herzog wisely let Kristin Beck do most of the talking, as we see her with friends and family going about her daily life.

One of the most fascinating parts of Kristin’s story is that her younger life as Christopher is also well documented, in home movies. We see her as both Christopher and Kristin training soldiers and police and doing construction projects at home. It’s the same person doing the same activities, but with a vastly different emotional outlook and, of course, different clothing.

Kristin’s father and siblings accept her fully. A military colleague says, “I have known Kris for 20 years, and that sister is my brother.” Her young niece relates better to Kristin than to Christopher.

“I see myself as a better person,” Kristin says. “I like myself better.” As Christopher, she was miserable and military bravado led to almost suicidal behavior.

The road to today was far from smooth. Kristin came out suddenly as transgender, showing up to work at the Pentagon in women’s clothing, and then coming out nationally on an Anderson Cooper CNN program. Getting hate mail and nasty comments on social media was an untested battlefront for her.

Transgender identity mystifies many people, but Kristin clues the audience in on something: It’s a bit of a mystery to her, too. When asked, “Why did you decide to become a woman?,” she responds, “Why did you decide to be born with blue eyes?”

Beck likens the question to someone who was born without sight, but can now see, being asked to describe a sunset.

“It’s difficult to put into words,” she explains.

Difficult, but Kristin Beck’s story may help everyone understand the experience just a little better.

The streets of Newark are tough on anybody, but they seem that much tougher if you’re a woman or LGBT. There’s violence. There’s homophobia. There’s sexual assault. It is not surprising that a group of young lesbians would look for some freedom and breathing room in the West Village just a PATH train away.

In August 2006, the last thing a group like this would expect in that storied place where they were free to be themselves — right in front of the IFC Center on Sixth Avenue and West Third Street — would be encountering a man threatening to “fuck them straight!” and then advancing on them physically. Or that they would be branded a “lesbian wolf pack” in screaming tabloid headlines after one of the girls stabbed him to fend off assault, while the others beat him.

The entire incident took only took four minutes to unfold but in its wake, the aggressive male was portrayed as a victim and four of the seven friends found themselves indicted for gang activity and villainized in the press.

The young women — Terrain Dandridge, Renata Hill, Venice Brown, and Patreese Johnson — did not take plea deals because they felt they were defending themselves. Meanwhile, newspapers ran headlines like “Attack of the Killer Lesbians” and Fox News fear-mongered about gay gangs out to “take over” and hurt bystanders. Evidence of self-defense was not presented at the women’s trial, even though the IFC security cameras suggested that’s how the incident blew up. They each spent years in prison.

“Out in the Night” spends a lot of time talking with the four women and their families. Johnson had a knife because her brothers wanted her to be able to protect herself — she had been assaulted before. After bad experiences with the Newark police, she said, “I am never calling 911 ever again.” Mistrust of the authorities and self-reliance learned the hard way were very much in play that night.

Hill, while in jail, wound up being treated for PTSD. The attack on that August night echoed a rape she suffered years before. “You become property of the state in prison,” she complains, pointing out that regulations even dictate her underwear choice — boxers are out. Six years in prison meant losing precious time with her young son.

For Johnson, time in prison is just “existing.”

Activists and attorneys over the years have emphasized the injustice of what happened to the “New Jersey 4,” but “Out in the Night” succeeds primarily because of its focus on face time with the four women and their families. It is hard not to be moved to tears learning their stories — and not to hear in their voices their truth and their innocence.

Most of us know him as Mr. Sulu on “Star Trek.” Others recognize his deep voice from “The Howard Stern Show.” Younger fans follow his Facebook musings. What many people (like me) might not know is that George Takei and his family were marked irrevocably by the years spent exiled by the US government in World War II internment camps. “Simply because we looked like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor,” as he says.

Through dashboard cams, film and TV clips, and interviews, we see Takei take on many challenges. He persevered as an actor, playing Asians at a time those roles went to white actors. Before coming out, he pressed for recognition of the injustices of the internment camps, seeking both an apology and reparations. In Los Angeles, he was a vocal advocate for mass transit.

In recent years, Takei was an activist fighting California’s Proposition 8.

We meet his husband Brad Altman (now Takei). The two men formed a family years before heir marriage was legal. Brad is now his manager –– Takei’s calendar is jammed with appearances and work. Old “Star Trek” colleagues marvel that Takei, 77, has pioneered new career opportunities.

Takei’s legacy project, “Allegiance,” is a musical that dramatizes his family’s experiences during their internment. Though his Facebook page made him a social media sensation and popularized his catchphrase “Oh my!,” he originally took to that platform to promote the play.

“Our history tells us we have a dynamic democracy, and I look forward to the time that equality is shared by all Americans,” Takei observes, and the late Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye is seen noting that Takei’s ability “to still love this country, after going through what he went through, is remarkable.” We learn that he learned endurance and resilience is from his father, whose leadership in the camp was an embodiment of gaman, the Buddhist concept of enduring extreme hardship with utmost dignity.

“To Be Takei”means to grow up learning the Pledge of Allegiance amid guard towers and guns, but still believing the in the American promise of equality and being willing to fight for it.

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL | Jun. 13-22 | ff.hrw.org

LADY VALOR: THE KRISTIN BECK STORY | Directed by Sandrine Orabona and Mark Herzog | Jun. 14 at 7 p.m. |IFC Center, 323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St. | ifccenter.com

Jun. 16 at 6:30 p.m. | Walter Reade Theatre, 165 West 65th St. | filmlinc.com

OUT IN THE NIGHT | Directed by blair doroshwalther | Jun. 18 at 7 p.m. | IFC Center, 323 Sixth Ave. at W. Third St. | ifccenter.com

Jun. 20 at 6:30 p.m. | Walter Reade Theatre, 165 West 65th St. | filmlinc.com

TO BE TAKEI | Directed by Jennifer Kroot | Jun. 15 at 6 p.m. | Walter Reade Theatre, 165 West 65th St. | filmlinc.com